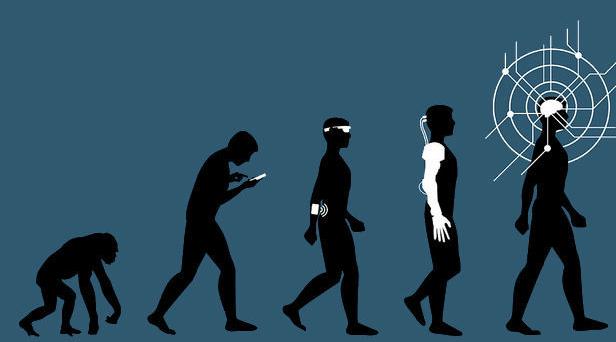

It has been said that culture becomes biology. When exactly culture transforms into biology is subject to debate, and forms the basis of cultural evolutionary theory – the study of human cultures over thousands of years.

But biology also changes across shorter time horizons – changing in ways that are less cultural and more economic. To the point at which economy becomes biology – something we have witnessed for more than a century as our world grows increasingly dependent upon technology.

A premise first introduced by Nobel Laureate Robert W. Fogel, technophysio evolution is the theory that our use of technology affects our body, and overtime, initiates its own set of evolutionary changes onto our bodies in response.

Technology has become so pervasive that it dictates our lives, and has effectively become our economy. If we adopt Fogel’s theory into today’s technology driven economy, then we can surmise that economy is biology.

Hence the importance given to social determinants of health, exemplifying why food deserts matter – why inner city violence leads to a greater prevalence of hypertension among urban minorities – why unemployment leads to higher overdose rates – and why Medicaid expansion leads to better patient outcomes.

If economy is biology, then economic policy determines long term patient health, with some policies faring better for patient outcomes than others.

We observed how the Affordable Care Act (ACA) changed health care in complex, unforeseen ways. With many of the benefits coming from mostly economic improvements among patients enjoying the expanded Medicaid benefits.

Now with the passing of the recent $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), healthcare is again set to change through another slew of economic reforms. And though the legislature was ostensibly designed to provide support for families during COVID-19, the long term economic shifts may come to dictate healthcare for the next decade. As the ARPA is an expansion of the ACA, building upon Obama era policies.

An analysis of the ARPA by Thompson Reuters finds that the ARPA expands ACA emergency care coverage, but eliminates any premium on emergency insurance (COBRA) coverage; increases the maximum amount of dependent care benefits that can be excluded from a person’s income tax; and offers greater tax credit while eliminating the upper income limits from participating in those credits.

All of which appears quite appealing, and may even incentivize states who previously chose not to participate in the ACA to expand their state’s Medicaid ACA program.

The think tank, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, believes the ARPA would help upper income brackets deal with insurance premium burdens and would help lower income brackets retain certain insurance cost benefits while also retaining their unemployment benefits.

At first blush the expanded offerings and coverage would provide meaningful help to those suffering in an unprecedented time of economic hardship and uncertainty. But all that glitters is not gold.

Some consider this a short-term fix for a long-term crisis, as the only clear path to expanding health insurance is more government subsidies for commercial health plans, which are the most costly form of coverage.

And the cost of healthcare expansion becomes more costly to the tax payer over time.

In an interview with NPR, Paul Starr, a Princeton University professor and health care policy expert said, “the expansion of coverage is the path of least resistance”, and dubbed this dynamic of expansion a, “health policy trap.”

Starr went on to say, “insurers don’t have much to lose. Hospitals don’t have much to lose. Pharmaceutical companies don’t have much to lose, but the result is you end up adding on to an incredibly expensive system.” Insinuating that the added costs create their own externalities which compound onto the existing costs – which means as the healthcare system expands, the increase in cost expands at a faster rate.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that by the end of 2021, taxpayers will shell out more than $8,500 for every American who gets a subsidized health plan through the ACA, which is an increase of 40% from the cost to taxpayers in 2020. An increase attributed to the expanded policy derived from the ARPA.

Proponents of this expansion argue that traditional Medicaid plans are still available, but the availability is becoming increasingly scarce as the healthcare industry shifts away from traditional Medicaid plans to now accepting a greater number of patients under the ACA.

Which is only logical since the healthcare industry stands to profit more per patient through insurance plans offered through the ACA than through traditional Medicaid programs.

According to the Health Care Cost Institute, health insurers in the Atlanta area pay primary care physicians $93 on average for a basic patient visit, but Georgia’s Medicaid program would pay the same physician seeing a patient covered by the government health plan just $41, according to the state’s fee schedule.

So why would a physician accept a Medicaid plan when it can accept an ACA plan?

So if an insurance company has to pay physicians more, then it will then charge the government more, and so too will the pharmaceutical company – and the medical device company – and the medical distribution company – and on it goes. And why not? The federal government is footing the bill.

Which explains the angst among many economists reluctant about the expansion of the ACA under the ARPA – how is the government going to finance this expansion? The simple answer is that they will continue to issue more debt and print more currency.

But healthcare operates differently in a debt-centric economy compared to a traditional capitalistic market. When debt fuels an economy, the separation among those who contribute to economic productivity and those who drive the economic cost widens. This means the social class which contributes to the economy, which finances the expanded healthcare system, grows more distinct from the social class which enjoys the benefit from the expanded system.

Soon there will be a distinct debtor class, which will grow accustomed to a perpetual debtor lifestyle, willingly taking on healthcare expense with little to no expectations of ever contributing to those expenses. Comfortably numb in the ever expanding sphere of healthcare coverage provided by the federal government.

And in turn, the healthcare industry will continue to charge more and more to this new debtor class, eagerly up-selling healthcare services to a class of patients willingly taking on more expensive insurance policies.

Soon we will begin to question the morality of medical debt, and whether it is ethical to continue to provide medical care to those who cannot actually afford to receive such care – creating a modern version of debtor’s prison based upon medical debt.

And as the disparity in healthcare economics increases, so will the disparity in healthcare outcomes.