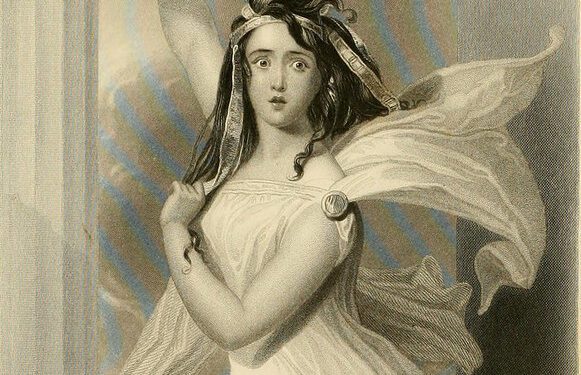

To have great foresight may appear to be a blessing. But if no one believes you, then that foresight quickly becomes a curse. History is riddled with such individuals, none more famous than the mythological Cassandra, the Trojan priestess fated by the Greek God Apollo to utter prophecies that would prove to be true but never believed.

Though her tale has been relegated to the annals of antiquity, her fate is shared among many today, particularly those disenfranchised in the opioid epidemic. For us, the truth is hardly much of a solace for the fate we are forced to endure. For many, it’s a literal curse.

We know the government’s fear laden approach to opioids is wrong. We know the clinical data. We see patients struggling and the lives leaving far too soon. But no one believes us. When we speak out, our words fall silent, discredited the moment they are uttered. We sense the seething stigma.

The unseeing public is trapped in a feedback loop, an echo chamber of circular logic. They think: If you truly need medication, you’ll get it. And if you don’t, then you won’t. It’s so simple, and so very wrong. Try telling the truth, and you’ll quickly be met with disbelief, if you’re lucky, and disdain, if you’re too honest.

So we suffer in silence, struggling to bear the burden of pain.

I wish to give a voice to the voiceless masses of Cassandra’s. Those patients who pray people would believe them, just for a moment, and understand their plight.

I wrote Burden of Pain for all the Cassandra’s, hoping their curse will one day be lifted and people will finally believe them.

Turn a curse into a blessing.

Excerpt:

Northwest Indiana is an all-American, blue-collar community that, like so many others throughout the country, fell victim to the opioid epidemic. You can read the statistics and study the facts, but until you’ve practiced clinical medicine in areas affected by the epidemic, you will not properly understand it. You will not know the shame of a person needing to work but unable to without pain pills, or the humiliation of having to choose between work or surgery, and often being left with only the recourse of pain pills as a viable solution.

Many of our patients were affected by the epidemic, directly and indirectly. We understood that impact on their lives. The pervasiveness of the epidemic made it a common topic of conversation. We talked openly and honestly with our patients. In doing so, we brought light to the dark, hidden difficulties in many patients’ lives.