Pain is both a clinical symptoms and subjective phenomenon, the two sharing a complex relationship with one another, as the underlying cause of pain is understood through the interpretation of that pain. A balance of perspectives then forms, which includes balances between good and evil, suffering or pleasure, and fundamental right versus wrong, each layering on top of the other, which CS Lewis describes as, “misery and misery’s shadow.” We understand our pain through these layers and simplify complex thoughts into a basic understanding equating pain with the concepts of badness or even evil. John Milton, author of Paradise Lost, who has probably influenced the narrative of pain as any clinician has, said, “pain is perfect misery, the worst of evils”, and even correlated pain as punishment in the name of justice: “of worse deeds, worse suffering must ensue.”

An interpretation of pain that influenced 19th century literature and medicine heavily. Victorian poet Robert Browning wrote a poem romanticizing a blood disorder, in which he defined the disease and the patient as having a relationship, which proved to be “pure and good”, mostly because the disease caused the patient in the poem no pain. Diseases were and always will be understood by its perception, even in the age of medical research. By the middle of the century, tuberculosis had become an epidemic in both Europe and America and much of what we learned about the disease – how the disease spreads, its mechanism of action – occurred during this time. But rather than focusing on the underlying germs that caused the disease, the public focused on the presentation of the “romantic disease” – the appearance of the people afflicted – and the thinning, pale faces became an infatuation that became a fashion trend that we continue to see on runways around the world today.

Even with modern clinical knowledge, we turn to literature and philosophy to understand pain. Russian author Leo Tolstoy, arguably the paramount philosopher-author in recent centuries, equated pain with morality. In his novel, The Death of Ivan Ilych, the protagonist expresses a sense of shame in taking opium for his pain, perceiving his lack of willingness to endure his pain to be a sin. A prevailing belief seen throughout history among religious philosophers such as Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, and CS Lewis – that the ability to endure pain is a moral virtue. That to bear pear is to bear a righteous suffering, which these philosophers perceived not as medical symptoms, but as virtues to display. CS called pain, “a load so heavy, only humility can carry it.”

But we did not always equate pain in such moralistic terms. Stoic philosophers from ancient Greece perceived pain as something to accept, not to react to, and advised that the perception we give pain is just that – a perception – which can change based on how we approach pain. The philosopher Epicurus advised that, “avoiding pain is not the same as pleasure seeking”, which embodies the rational, balanced perspective of pain many stoic philosophers. Including the philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius, who wrote, “whenever you suffer pain, keep in mind that it is nothing to be ashamed of”, and advocated that pain is something to be overcome through discipline and perseverance.

Two differing interpretations of pain, to which we have added layers as we have continued to shape our perspectives in the world. And no modern perspective has done more to influence our interpretation of pain than the philosophy of Humanism, the philosophy that forms the basis of our modern educational system, which promotes an individualized, subjective perspective of pain, as exemplified by the French Humanist, Rousseau who wrote, “what I feel is good, is good, and what I feel is bad, is bad”, internalizing the perception of pain with his direct experiences of pain. Which is how we interpret pain in healthcare today, through the pain experience. But experience is more than an objective account for what is felt in the moment. It is a complex combination of current and past perceptions each imbued with both objective memories and subjective emotions.

Pain research has shown the relationship with a provider affects the level of pain a patient experience, making pain both a real condition and a state of mind. Pain is understood in relative terms, in relation to a prior experience, either directly or indirectly – and our experience of pain is the most readily available interpretation of that experience, our own Ockham’s Razor.

Neuroscientist VS Ramachandran believes pain is an opinion, and much like our opinions change, so does our perception of pain, being based on the present experience of pain and our reflections of pain after the fact. The changing perspectives of pain based on time, past and present, makes it appear as two different things, as a duality, leading both CS Lewis and Emerson to describe pain in terms of the pain itself and the shadow it casts.

Pain does not only relate to the underlying injury or disease; it is a figurative conversation among all the layers of perception and the factors causing the pain. Which explains why studies have shown people in love feel less pain, but people in the grasps of fear feel more pain. A study comparing similar injuries between war veterans and civilians found that only 32% of the veterans versus 83% of the civilians requested pain medications for their respective injuries, with the authors concluding the past experiences of war veterans led to a higher pain tolerance – but you can also conclude that the inclination to even ask for pain medications in the first place is based on perceptions that differ with different experiences, regardless of the tolerance levels.

Pain is based on changing interpretations that become reinterpretations as built layer upon layer of different perceptions, that in the moment appears vividly real, a phenomenon Swami Vivekananda calls our journey from “truth to truth.” A dynamically changing process in which we are just in one of many phases. Which makes our modern quest to cure pain just another interpretation, and our search to go beyond opioids simply adding another layer of scientific veneer to our existing, more abstract notions of pain.

Pain will always be a relative to the person experiencing it, and our attempts to study pain in biochemical terms will always be incomplete without studying the dynamic perceptions of pain that correlate with the biochemistry of pain, as the pendulum of perception will always perceive any medical breakthrough from the perspective in which the string is held.

For many patients, who endure pain as part of their daily lives, their perceptions of pain are an eclectic mix of all these perspectives drawn over time and superimposed onto the daily existential angst of their lives. Some see pain as something to overcome, perceiving their self-worth based upon their ability to overcome. Some see pain as an unfair burden placed upon them, seeing relief from pain as a right to which they are entitled. These interpretations largely influence patient behavior, and correspondingly, provider reaction.

We laud patient resilience when we see a patient overcoming a debilitating injury. In Oliver Sack’s story, we admire the patient’s ability to continue playing an instrument despite his worsening neurological conditions. But we just as quickly recontextualize resiliency into the shame of stubbornness for other medical conditions. In Jhumpa Lahiri’s story, The Treatment of Bibi Haldar, we observe how the same characteristics of resiliency are met with scorn as the protagonist, Bibi sought her own treatment options for her neurological conditions despite facing resistance from her neighbors, having to overcome social disgrace in order to be healed.

A unique, Faustian bargain of self-justification forms when patients are caught in the conflict of interpretations between the individual needs of their medical conditions and the broader social perceptions of their medical conditions. Many of these patients shoulder an undue burden imposed upon them due to the uncertainty arising from their medical conditions. A burden of uncertainty that forms from the incomplete interpretations of pain and addiction, prompting its own set of reactions from patients. Reactions that we should divert into positive opportunities for patient growth.

Victor Frankl, author of Will to Meaning, a book detailing his experiences during Nazis interment and the philosophies he developed, acknowledged that adversity is not evenly distributed, but facing such burdens creates opportunities to respond either positively or negatively. How we make decisions, the way we decide, gives us an opportunity to overcome the adversity. Which makes the decisions as important as the adversity – and the perspectives through which people make decisions equally important, beginning with the awareness of those perspective.

When former NBA player Chris Herron openly discusses his opioid dependencies, he creates the impression that discussing opioid abuse is permissible. When Dr. Rana Awdish shares her experiences with opioid dependencies post-surgery, and the cognitive dissonance it created, she empowers other healthcare professionals to understand rather than to judge addiction medicine. Awareness will help us understand that pain and addiction are merely different characteristics of the same underlying medical conditions, which both should be viewed from the perspective of clinical care, not criminal prosecutions.

Addiction is an experience as much as pain is an experience, and the transition from one experience to another is a poorly understood process that should be studied much like pain itself should be studied – as a combination of the medical research that study the biochemistry of addiction and the interpretations that define our comprehensive understanding of addiction. A provider is more likely to trust a patient who strives to be honest, just like a patient is more comfortable with a provider who implicitly trusts, and the relationship that develops over multiple encounters focuses on medical care above all else, largely because the trust enables that focus.

Chronic pain patients, when reflecting on their experiences of pain, nearly always distill their entire, prolonged experience with pain from the perspective of two points: the peak pain experience and the last pain experience. Which correlates to many literary interpretations of pain, in which the experience is seen from two perspectives, that behavioral economists are its most intense form and its most recent form.

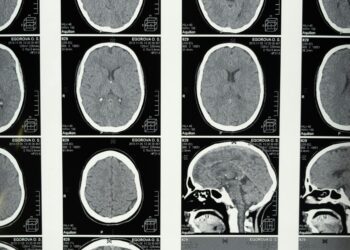

The multiple perspectives of pain make trust all the more imperative for medically appropriate patient care, for us to understand the complexities within each patient encounter. “Pain is to be understood analytically and conceptually”, a quotation by none other than the cartographer of pain, Dr. Ronald Melzack, the pioneer of modern pain management. His more conceptual work centered around two main concepts, standardizing the interpretation of pain through a numerical system, and building a repository of vocabulary to help patients express their pain, believing that the ability to express pain helps to define the presentation of pain. Most of us can remember being asked what our pain level is based upon a scale from one to ten, but hardly any of us can recall being asked to describe our symptoms in as many words as possible. But for Dr. Melzack, both sets of information were equally important, as he understood pain to be a symptom and a linguistic label.

Words matter, and the patient narrative is the interpretive journey by which they transform symptoms as experiences into a coherent story, and how that story is told is just as important as what is in the story. Something sociologist Studs Terkel observed when he chronicled the stories of everyday Americans. The words we use convey the thoughts we think, and our experiences of pain, and our overall health. For many pain is a constant companion, and simply validating the presence of pain helps to reduce the pain, highlighting the importance of awareness.

When you become aware of all the perceptions that go into a specific decision or action, you start to see the relationships that form among all the layers of interpretations. For most of the history of healthcare, we have looked at awareness as mostly a concept to aspire for, and left it at that – leaving patient care in the throes of interpretation and reaction. But with healthcare growing increasingly complex, we need to bring structure to the complexity, and structure our awareness to healthcare decision-making.