“Let them eat cake”, is quite possibly the most famous misattributed quotation given to any person in modern times. The person to whom the quotation is falsely attributed, Marie Antoinette, was already a reviled figure in pre-revolutionary France, and the perception that she was an out-of-touch elitist who did not understand the plight of the common person made this rumor seem all the more true, and all the more tantalizing not to share.

Eventually perception became reality, and the quotation became firmly entrenched to Marie Antoinette, and soon the quotation became a symbol of the gross inequity in French society – which led to a violent revolution leading many to lose their lives through of the most gruesome tools of execution, the guillotine. A revolution waiting for its initial igniting spark – that it found in an off-kilter remark, that came to symbolize much more than its words would have intended.

That is the power of perception. And while the aphorism, perception is greater than reality, has been used to the point of cliché, it nevertheless remains absolutely true.

And for this election cycle, perhaps the perception of voter safety will be the absolute deciding factor in determining who our next president will be.

It will determine who goes out to vote, and consequently, the total number of votes each candidate receives. If people feel the risk of contracting COVID-19 or the risk of suffering personal harm due to civic unrest or outright riots is too great, then voter turnout will be disproportionately affected. Of the two, I believe the former, the perception of public safety due to COVID-19 will be the bigger factor in influencing voter turnout.

Though a Rasmussen poll early in the Summer of 2020 found that nearly half of Americans believe that community violence is a risk in their communities – a statistic quite appalling – it is one that is not likely to change in the remaining weeks prior to the election.

What is likely to change, and change in a significant way, is the impact of COVID-19 on the everyday lives of Americans. A change that will have serious bearing on the voter turnout, far more than any risk of communal violence – because such a change will come in just weeks, if not days, before the election itself. Relatively recent – which makes it far more impactful.

Recency bias has been studied extensively by behavioral economists in nearly all facets of life, repeatedly proving that recent events hold greater sway than older, more historic events. A phenomenon that has come to shape much of our society, from closing arguments in legal courts to sales pitches targeting customers.

Recency bias creates predictable responses among the people affected – which, for voters, can be used to predict or in the very least, approximate, voter turnout based upon the progression of COVID-19.

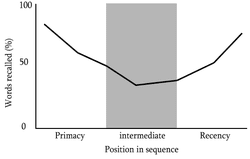

The graph displayed is  the Serial Position Effect, a term coined by Hermann Ebbinghaus and shows a wide, U-shaped curve. The graph was developed based upon numerous studies showing we tend to remember the first and last things more easily. Which for most seems obvious enough.

the Serial Position Effect, a term coined by Hermann Ebbinghaus and shows a wide, U-shaped curve. The graph was developed based upon numerous studies showing we tend to remember the first and last things more easily. Which for most seems obvious enough.

But what is not obvious are the factors that have shown to adjust the angle of the curve. Factors that can impact the effect of the recency bias on voters. The first is the overall intensity of the recency bias.

Is it far more severe or significant than other news we heard before?

If COVID-19 becomes far more virulent in the coming days than it has been before, then the impact of recency bias will become more pronounced. But that is not predictable, and the numerous revisions recurring among predictive models show just how unpredictable it is.

But what is predictable, and an equally signficant factor, is the duration of the recency bias. Studies have shown that recency bias depends upon both the intensity and the duration. And the impact of the duration is related to the ratio of the recency bias period relative to the entire period of exposure.

Translated into COVID-19 terms, the impact of the recency bias depends upon when COVID-19 gets worse. While estimates vary, most believe that COVID-19 really became a national issue sometime in March, with many economic shut-down periods beginning in April. So if we assume March to be the beginning, admittedly that is a challengeable assumption, then the pandemic has been going on for seven months. If the pandemic worsens in early October, then the recency bias ratio would be one month to seven months, or 1:7. If the pandemic worsens in late October, then the ratio would be less.

How less does it need to be to be negligible? That is the critical question.

We will never be able to predict true intensity and duration with such a short time interval, but the statistics can provide a proxy. And with these two points we can create parameters around understanding the impact of COVID-19 on voter perception.

Politics is rife with precedent, and October during presidential election years has been fertile ground for scandals and news. In fact, the term “October Surprise” was coined by political strategist, William Casey, to reflect the frequency of this phenomenon in modern politics. Indeed, nearly every election since the 1980’s has had some deliberately placed scandal designed to affect the election.

What makes 2020 unique is that the COVID-19 is not inherently political, but has become political through an entanglement of public policy, inter-department rivalries, and a wide array of public opinions and conspiracies. And the direction COVID-19 takes this October will likely be the October Surprise that determines the election.

To validate our assumptions, we will host a series of survey polls, administered through our own news outlet, to glean public feedback verifying our core assumptions.

To quantify the impact of voter safety we focus on two key metrics: daily death rates and daily cases of COVID-19. We use the metrics defined historically by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

The survey below assesses voters’ perception of safety based upon different daily death rates and incidence reports. And the goal is to determine the relative impact of COVID-19 on voter turnout based upon the severity of the pandemic and when it begins to worsen. Survey results will be updated on a weekly basis until the election.

And hopefully by understanding voter perceptions and behaviors, we can ensure a safe and fair election for everybody.