The Great Schism of 1054 divided Christianity and formed the foundations for Catholicism and Orthodox Christianity. It was the culmination of theological and political differences that developed during the preceding centuries between the religious leaders and kings of the Latin West and the Greek East. Which at first began over seemingly small squabbles, really more differences of opinion, that manifested over the course of converting religious arguments into political arguments and back again, into irreconcilable differences that led to a permanent partition.

For Christians living in that period, the schism was seen as nothing more than political grandstanding, nothing like the permanence we see today. But the failure to see the schism’s impact led to centuries of conflict, war, and acts of atrocities that came at the cost of hundreds of thousands of lives – exemplifying the power of unintended consequences.

A law, often cited but rarely defined, that states the actions of groups of people, such as governments, always have effects that are unanticipated or unintended. And largely emanates from the disconnect between individual actions and group benefits.

For the leaders of Medieval Europe, it led to the permanent partition between Eastern and Western religions, that eventually prompted political, cultural, and linguistic separations.

For the different departments within the United States Federal government, the disjointed, apparently contradictory responses to the COVID-19 pandemic will prove far more deleterious, in the long term, to the health of Americans than COVID-19.

We have health policy experts calling for additional COVID-19 reimbursement codes that support additional testing, educational visits, and even more telemedicine visits. The American Medical Association and various physician advocacy groups have established guidelines and documentation recommendations to optimize the utilization and reimbursement coverage for these telehealth codes. All of which point to an already well-established pending uptick in the number of cases and projected mortality. Which is to say – COVID-19 is likely to get worse.

Something we know – really, have known for a while – which makes the Federal Government’s economic response curious, to say the least. The government has doled out billions of dollars and has propped upon the financial markets with the allure of low cost capital, but economic growth remains stagnant. The tried and true solution to any recession is to encourage consumer spending, but that would mean consumers have to spend – something they are ostensibly not doing, nor have any plans to do at the levels required, despite the upcoming holiday season. Consumer surveys on expectations for holiday shopping projects to be far below average, even after discounting for the pandemic. An incongruency that only raises more questions about the stimulus package debated on Capitol Hill.

The unexpectedly ineffective response to the previous government stimuli is due to the fact the economic downfall caused by COVID-19 is not a true recession, as economists would define it. But we seem to be treating it as though it were. So the government injects capital into the public, hoping the public will spend the capital and stimulate the economy. But consumers are not leaving their homes, and consumer spending is not spurring the economy as anticipated.

Something the healthcare policy experts already know, and are anticipating and responding with an increase in codes that reflect these behavioral changes. Putting the economic response squarely at odds with the clinical response.

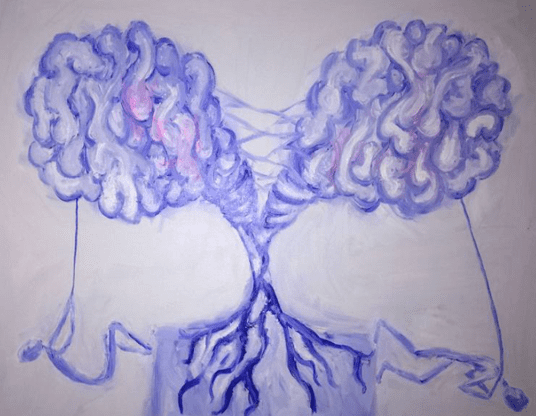

A modern-day schism.

Which can easily be laughed off as another example of how disconnected the politicians are from the public. If not for the consequences of these poor decisions.

If the government continues to dole out capital at this pace, government debt will continue to rise and worker productivity will decrease – prolonging the economic recovery.

A lot of this seems like broad policy issues with little to no bearing on the average patient. And in the short term, most would be right. But in the long term, when COVID-19 is quarantined to the history books, the effects of higher debt have significant adverse healthcare effects for decades to come.

High financial debt is associated with higher perceived stress and depression, more comorbidities, and higher diastolic blood pressure. These associations remain significant across different socioeconomic status, psychological and physical health, and other demographic factors – suggesting debt is an important socioeconomic determinant of health.

As important as other social issues that we are starting to learn are also healthcare issues.

Healthcare policy makers, who can foresee the change in patient behavior should respond with more than just new reimbursement codes. Policy makers who know better should do a better job educating the political leaders about the economic effects of their decisions.

FDA head, Dr. Hahn assures us that the FDA will make decisions based upon science – begging the question where science ends and policy begins. Or are the two inextricably linked during the pandemic to be indistinguishable?

For the public, the answer is a resounding yes. The public currently makes consumer decisions as patients, altering the response stimulus checks from spending to saving. Therefore, to approximate consumer spending, think of the public as a mass of patients, not as consumers in the traditional sense.

Rather than injecting capital hoping for a stimulus of spending, identify truly impactful economic support that would help patients in the short term and long term. We as a country already have a dangerous relationship with debt, and we cannot let mistakes derived from conflicting policies manifest as added debt.

As the debt burden we are creating will be passed along to the consumer who will then bear the healthcare burden that comes with added debt. So while we may believe we are helping people by encouraging spending, we are simply supporting the growth of debt, and the healthcare consequences that ensue – embodying the law of unintended consequences through a modern day schism.

A schism that puts economic policy squarely at odds with healthcare policy – igniting an unforeseen chain of events that will put many people in an awkward position of choosing their health or their livelihood.

A schism that may initially appear as harmless as the Church schism of 1054, until the effects of the split begin to manifest as debt.