To predict the future, focus on what you don’t know, rather than what you do know – prioritize the uncertainty.

A conceptual framework proving surprisingly accurate, at least when it comes to the pandemic, after all we have policy makers who decry the need for masks because – according to them – mask-wearing may deter vaccinations. A counterintuitive logical exercise which assumes patient behavior follows some variation of the law of unintended consequences.

So – following their logic – when we enact healthcare policy, we should assume patients will respond to the uncertainty within the policy. Maybe they’re right. It then follows that to predict patient behavior, we should focus on the uncertainty.

Easier said than done – how often do we think or consciously make decisions like that?

We decide based upon what we think we know, whether that is all to know or not.

Our knowledge is flawed, therefore our predictions are flawed just as well.

When we hear multiple predictive models anticipating an upswing in COVID-19 mortality this Fall – 3x mortality to be specific – what do we make of that information?

We know these models have been off before, and everything around us seems to imply the pandemic is in the past. But what if we’re wrong?

What if the pandemic is simply in a lull, transitioning from one phase to another, and what we perceive to be the end is simply the interlude?

We just don’t know, and while we can sing sweet rhetoricals until our throats sore, we still will never know with any certainty.

Maybe that’s the point – and the policy-makers are on to something. Maybe instead of trying to predict what will happen, we should focus on what we don’t know, and try to navigate the most likely outcome based upon how uncertain we are.

Thinking like this quickly becomes abstract, and it may help to think figuratively.

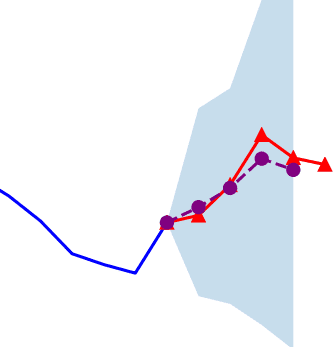

Uncertainty is like a slope, with different gradients – some sharper than others – and the sharper the slope, the greater the uncertainty.

Some uncertainty is more uncertain, coming at a greater gradient, while other forms of uncertainty are less uncertain, and with lesser gradient.

Typically the future follows the path of least resistance, trending towards an uncertainty with a lesser gradient. So to predict the future, just gauge what you are least unsure of, as that is the likely course of action.

To predict the future of the pandemic this fall, ask – what are we least unsure of?

We know people are fed up with the pandemic, and generally unwilling to adhere to social distancing and mask-wearing protocol.

We know vaccinations have hit a wall, with a clear divide forming between those who have received the vaccine and those who are not willing to receive it.

And we know the virus continues to spread. Whether it is the delta variant, or another downstream Greek letter affiliate, the virus is mutating and continues to spread.

Of the three factors cited, the first two are relatively predictable. We can generally anticipate how people will behave regardless of how COVID-19 progresses, because we are confident that certain past behavior will mimic future actions.

What we are most unsure of is the virality of the variants. The available data suggests the virus is more infectious, spreads more easily, but the severity of the disease seems to be tempered a bit – at least among the vaccinated, not the unvaccinated.

This distinction may appear obvious, but is most critical.

Remember, even at the peak of the pandemic’s first and second wave, the most devastating impact of the virus was the sheer burden it placed on the healthcare system. Social distancing measures were enacted largely to distribute the burden over time, giving healthcare providers and hospitals much needed space and time to address each individual infected.

Since the total number of unvaccinated patients is less than the entire population, it would appear that even if the virus spreads at a faster rate, the disease burden may be less than what it was at its peak.

Yet this the crucible upon which all COVID-19 predictions hinge.

There will come a point, either at the end of October or the beginning of November, in which virus-related mortality will spike. How quickly and how severe that upswing forms will determine how well the healthcare system can manage it.

If this prospective peak is less than the overall capacity, then the healthcare system can withstand a Fall surge. If it is greater, then we will start to see shades of what we saw in early 2020 – lockdowns and all – not exactly the same, but similar.

How similar?

Well that’s what we are uncertain about. But at least we know what hangs in the balance.

At least we know what we are uncertain about.