Trust is never trust alone.

It is the absence of distrust, sufficiently absent to the point at which we can comfortably trust. Both of which – trust and distrust – are fundamentally perceptions, subjective and not always rational. We think we can trust someone because we think we should not distrust them.

It is just that simple.

But shifts in trust from one thing into another, or the varying trust we have in another person is quite complex, changing in ways we are not aware of nor recognize.

When cryptocurrency first came into public domain, it was largely relegated into the realm of internet conspiracy and mystique. And only those intimately familiar with the far reaches of the internet actually got involved in it.

But when the financial crisis hit just over a decade ago, the public lost trust in traditional financial institutions – though something else happened as well.

Not only did we lose trust, we shifted our trust away from traditional financial institutions and more into decentralized financial institutions. Cryptocurrency became more acceptable. In fact, certain cryptocurrencies became mainstream. We all know of, or at least have heard of, cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin or Ethereum. We may not have invested in them, but we are at least familiar with them.

Overtime, as we heard more and more about cryptocurrencies, we grew to accept them – and the more we heard, the more we learned. Now we have startups in healthcare promising to integrate the security of block chain technology (an aspect of cryptocurrencies) into medical record data exchanges. We have prominent entrepreneurs like Elon Musk investing heavily into cryptocurrencies.

The more we hear about something, the more we legitimize it. This is nothing new. It is the soul of propaganda, and the internet is rife with stories that went viral based upon nothing more than false rumors and speculation.

This is something the whole world experienced during the pandemic. Healthcare institutions lost credibility as they struggled to understand COVID-19 while disentangling healthcare policy from politics. Public trust soon shifted into an array of decentralized, online sources that at times correctly refuted false claims about the virus, and at times perpetuated a whole host of new conspiracy theories.

We know this story; we saw it unfolding in real time. But we have yet to understand the long-term implications of this trend. Healthcare will face enormous pressures from populist sentiment – and from previously discredited sources that have regained legitimacy as the public shifts its trust away from traditional institutions in healthcare.

In late 2020, Dr. Dhruv Khullar wrote in the Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA) about the decrease in trust in healthcare. He attributes the recent pandemic-driven decline in trust to a preexisting trend of decreasing trust in healthcare that has been ongoing for years.

He states the reasons are manifold and include numerous, mostly political and economic trends. Among which are – skepticism of authority and institutions; the spread of misinformation; fracturing of the modern media environment; and high levels of economic inequality and political polarization.

All of which seem plausible, and at a broad level are hard to disagree with. But he fails to identify any one particular cause contributing to this trend.

This is the true problem – the solution lies not in addressing the broad claims, but in addressing the granular process through which these broad claims form. The bits and pieces that come together to form the patient narratives that drive patient behavior – and create the distrust.

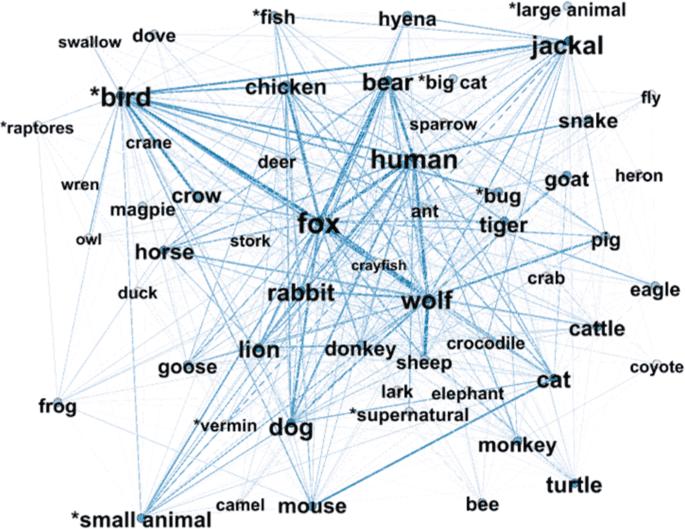

A phenomenon studied in depth by computational folklorist, Timothy Tangherlini, who describes this behavior as a narrative framework. He studied online behavior among those who engage in viral, internet-driven conspiracy theories, and identified patterns of groupthink among internet users, by focusing on the growth and development of conspiracies.

He notes that rather than any one website, or any one social media source, it is the interaction of multiple sources of information, superimposed upon each other in a specific pattern, which transforms an online conspiracy theory into something more.

“You’ve got these [multiple] domains that wouldn’t really interact, but they have alignments between them and those became important”, Tangherlini said. The connections between the sources, the patterns through which people jump from website to social media feed, or from website to website determine the strength of the belief in the conspiracy.

While Tangherlini acknowledges that tracing an individual’s patterns of internet use produces plenty of noise, he argues that through the noise we can find meaningful patterns that elucidate how strongly a person perceives the content consumed online. Patterns that emerge by analyzing multiple, disjointed points of interaction over time, and charting the unique structures and relationships.

A person who reviews the World Health Organization’s (WHO) guidelines on wearing masks online, who then goes on to read online content about oral, fungal infections secondary to mask use may be less compliant with mask guidelines than someone who reviews the WHO guidelines but then researches tourist destinations that have the best COVID-19 protocols set in place.

The predicted behavior – that person’s belief in the importance of wearing masks – is seen not through the websites visited, but in the pattern of traversing from one website to the next.

Narrative frameworks will become increasingly important as healthcare becomes more digital and healthcare trust becomes more decentralized. New social pressures have started to emerge, including the heightened awareness of racial injustice within healthcare, all of which will play a large role in dictating patient behavior.

Studying how patients consume content online and making meaningful extrapolations from those patterns will become essential aspects of patient care.

When we study patient behavior on the internet, particularly their patterns of online consumption, we understand how they perceive their health. How people use the internet affects how they learn from the internet – what they trust – and eventually the interaction between a patient’s experiences in healthcare and his or her internet use impacts individual patient decision-making – which in aggregate impacts healthcare outcomes.

Something healthcare policy experts should quickly realize. One of the major metrics healthcare policy wonks focus on is the cost curve, a measure of the amount of time and resources needed to improve patient outcomes. The cost curve assumes that the more time and resources expended, the better the patients’ outcomes. And for our economically constraint healthcare system, we strive to improve outcomes while reducing time and resources expended – bending the cost curve to be as efficient as possible.

Insurance policies are created based upon this premise, which should now account for the time patients spend online consuming healthcare content. The Annals of Internal Medicine found that the average patient encounter lasts sixteen (16) minutes, and the firm, Digital Information Watch, found that people spend on average one hundred and twenty-six (126) minutes online daily.

Insurance companies could glean meaningful information about patient adherence or of the likelihood of medical complications by studying the patterns of online consumption, and by correlating particular patterns of online use with better or worse outcomes – subsequently using that information to allocate additional time and resources to patients who may be at higher risk.

Going forward, healthcare will be more decentralized and populist – and increasingly influenced by popular healthcare trends online, swaying patient behavior. Until we develop frameworks that study patterns of online consumption alongside healthcare outcomes, we can only describe such phenomenon in broad, overarching terms.

Not in the granular, detailed context needed to meaningfully improve patient care.