Healthcare is not warfare, but we see literal allusions to war throughout healthcare.

When we visit the emergency department, we are initially triaged, a term alluding to a wartime healthcare system first developed by the French during the Napoleonic wars to tend for those wounded in battle.

During the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when then Surgeon General Dr. Jerome Adams urged all of healthcare to defer elective procedures and surgeries to treat those who were immediately infected with COVID-19, he called it a Pearl Harbor moment.

We cannot escape the literal militarization of healthcare. The word play is everywhere. Whenever some public health issue emerges or acutely worsens, policy experts declare some figurative war, as though heightened aggression is the solution.

We had the war against infectious diseases. We have the war against drugs.

The first led to an abundance of antibiotics in healthcare, to where we now have multi-drug resistant infections killing hundreds of thousands of people per year.

The second led to the criminalization of mental health conditions and a culture of medical McCarthyism in healthcare, to where we now have the highest number of overdose deaths in a year.

Clearly we are losing these figurative wars. But the real battle is not against some external enemy that we contrive in our minds, it is against our own minds.

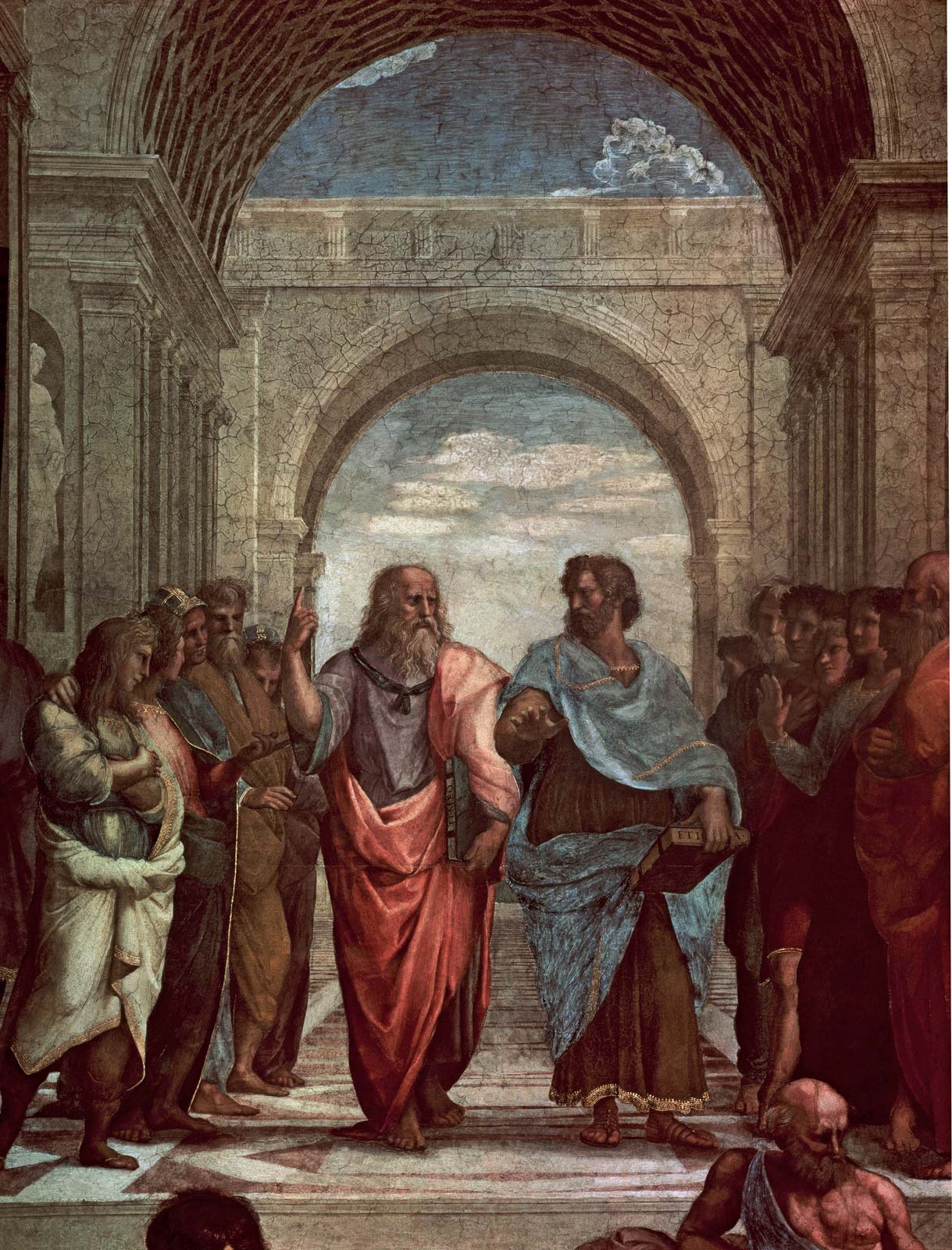

This is why language matters – how we think, we talk and how we talk, we think. Aristotle first noted this circular pattern between the thoughts we hold and the words we speak. And it has since been corroborated by Linguistics experts in recent decades.

Yet it has only recently been acknowledged as a problem in healthcare. In October 2021, the AMA Center for Health Equity and the Association of American Medical Colleges, through its Center for Health Justice, released a new health equity guide to language: “Advancing Health Equity: A Guide to Language, Narrative, and Concepts”

The guide provides suggestions and points of emphasis for physicians and healthcare providers when communicating with patients or vulnerable peoples in society. It emphasizes compassion in communication and a certain sensibility when speaking with someone who may be sensitive to verbal abuse or harmful labeling.

But this is not how many viewed the report. Many professional pontificators condemned the report as another instance of liberal excess in healthcare, decrying the report as a loss of free speech and as some form of harm against patients and healthcare providers who enjoy speaking in more blunt terms.

But free speech is different from structured speech. Just like effective communication takes into account both the speaker and the listener. Those who criticize the report try to simplify medicine into catch phrases and buzzwords. They cannot understand the nuanced difference in referring to someone who is experiencing homelessness to someone who is homeless.

These are also the same people who continue to declare figurative wars in healthcare.

When we fail to understand the complex nature of healthcare behavior and language, we tend to simplify healthcare. And when we simplify it, we create false equivalencies in our mind.

The real power of language in healthcare is not in how we speak, but in how we think. When we declare war on bacteria or on drugs, we know that we are not engaging in direct warfare in the traditional sense. But we implicitly become more aggressive. And that assumed understanding impacts our decisions.

We are less likely to provide equivalent quality of care to a discriminated minority than to a Caucasian male. Yet hardly anyone would declare healthcare as an institution or the physicians practicing medicine as racists. But we see persisting racial disparities in healthcare – anecdotally at an individual level and broadly through healthcare outcome metrics.

When we structure healthcare language, we structure how we think. When we optimize the patterns of thinking, we make better clinical decisions. The relationship is nuanced and difficult for many outside of healthcare to understand.

But those who practice medicine or are active in healthcare policy know that implicit biases in healthcare emerge from subtle patterns of thinking, below the level of conscious awareness. They are hard to address because they are hard to find.

But they become easier to discern when we actively structure how we speak.