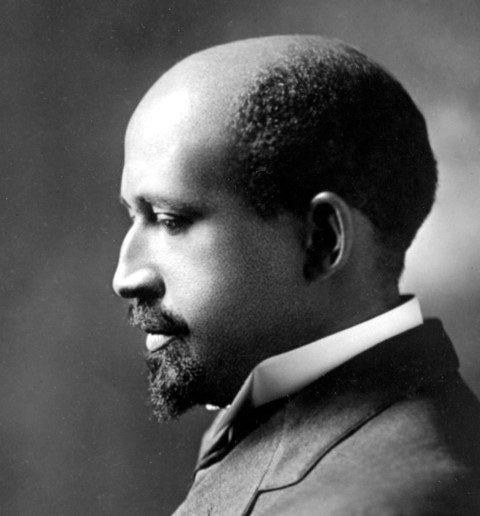

W.E.B. Dubois once told me that all Black souls have a duality – one side that is American, and another side that is Black American. Well he did not tell me, per se, I read it in a book. But the book spoke to me, so I consider that to be Dubois speaking to me. In fact, his words resonate so strongly within me that I see his words all around me, even in places you would least expect.

Take, for example, the emergency room at City Hospital. The name is a bit of a misnomer as the hospital does not really serve the city – as a whole – just certain parts of the city, the parts of the city most try to avoid, or otherwise drive through with the doors locked. We call those parts the wild 100’s, which originally derived their name from the street blocks that are labelled in the hundreds, but you can call it by whatever word or phrase that suits you – Section 8, underserved, impoverished, or just plain Black.

And there is a reason we call it ‘wild’, which can be found in the hospital’s emergency room as it sees every bit of the wildness. We have diabetics whose sugar spikes more than the stock market, hypertensives that would rather lose a foot than a dollar on medications, and of course, the trauma patients. You can write a book on every trauma patient that comes into the emergency room and weave a tale of healthcare disparity, political stagnation, and lack of economic opportunity. But in this squalor of society, one home grown boy, who is now a man, has chosen to establish his line of work: Dr. Erik Wilson.

He grew up not too far from City Hospital and vowed to make a difference. And he did, first academically and then professionally. He worked his way through school, all the while supporting both his family and his higher education prospects by obtaining scholarships to attend a school reserved for monied east coast elites. Once out east, he flourished even more, completing medical school, and becoming a trauma surgeon. He then began his clinical practice in an affluent neighborhood close to where he went to college, mentoring other students while building his practice. But there was a limit to how much he could build, as there is a limit to the amount of trauma seen in areas of affluence in this country. There are only so many housewives who hit their heads while drinking overpriced wine to go around.

Dr. Wilson needed more – so he thought about going home, like the prodigal son. But he never felt lost, though he felt concerned about returning home and entangling with aspects of his childhood neighborhood. He let his concern linger, but eventually, being a risk prone surgeon, he returned home. And, as is typical of his nature, he succeeded. He succeeded so much that his success became the hospital’s success, and City Hospital became a renown trauma center.

Which may not come as a surprise to you, but to me, and everybody in these parts, is a near miracle. City Hospital was known as a place you go to die, and if you have some sort of trauma, this is the place you go to in order to die quickly. Well that was the perception, but now we know this is the place to go if you have trauma – and want to get better. And long after we figured it out, all the media outlets and rating agencies figured it out and gave the hospital a variety of national accolades – like that matters. The same patients come to the emergency room and that will never change, no matter how the perception changes.

And Dr. Wilson knows that the most. Throughout the rise of the trauma division, he remained his meticulous, steadfast self; and by staying grounded, he only accelerated the stellar rise. Overtime he did develop different mannerisms, probably the most unique of which includes taking time for small talk, a habit he has long detested, seeing it as nothing more than an excuse to waste time. But with his name being known, and his reputation preceding him, such conversations became inevitable.

As in the case when a trauma patient who arrived around two o’clock in the morning with five gun shot wounds in the posterior hip, claiming to have been walking home from church when two strangers randomly approached him and open fired without asking questions. An odd story, no doubt, that becomes even more odd when you realize the context – well less odd, depending on your perspective. Leaving church at two in the morning is the typical story for gang members who are shot in their normal course of business – which they shameless tell emergency room providers to receive care without disclosing the nature of their business. As for five bullets in one specific region of the body – well, you do not get shot in the ass repeatedly unless you are in the game deep – ass deep. So that part is not as odd to me, as it might be to you, given how often we see gang violence around these parts. What strikes me as most odd is the patient’s request to speak to Dr. Wilson specifically.

This patient is named Tyrone Wilson, and his story is about as opposite as Dr. Wilson’s story as stories can get – diametrically opposite. Tyrone grew up in the same neighborhood as Dr. Wilson, though Tyrone was ten years younger. And growing up, Tyrone enjoyed school and possessed a similar academic bent as Dr. Wilson. But when it came time to apply for colleges, Tyrone did not have the same scholarship opportunities as Dr. Wilson since the state’s budget changed over the course of the decade leaving less funds for scholarships, leaving less opportunity for Tyrone.

So, whereas Dr. Wilson saw opportunity in the scholarships granted, Tyrone saw failure in the scholarships rejected, and internalized the failure as a testament of self-worth, particularly when he piled the scholarship rejection letters next to the college admission letters.

As the saying goes, money is the root of all evils, and Tyrone needed money for college so he entertained one of the biggest evils in his neighborhood, drug dealing. Smart, diligent with numbers, and applying the same meticulous work ethic to his new-found illicit trade as he did towards the academic disciplines, he quickly grew successful. Too successful.

As his income grew, so did the attention he garnered, and soon police agents arrested him at school after an anonymous tip told the police they would find drugs in his backpack. The repercussions drummed on like a college marching band: withdrawal of college admissions, expulsion from school, and three years of probation with a high likelihood of jail on the next offense.

Tyrone was devastated, but that is how it goes in the wild 100’s. The margin of error is razor thin and forces can conspire with or against you without you even knowing. The state funding went one way for Dr. Wilson and another way for Tyrone. And consequently, Dr. Wilson avoided an environment that Tyrone eventually acclimated into.

And over the years, Tyrone had his ups and downs as he navigated the volatility of street drug dealing. His recent dilemma, the one with the gunshot wounds, came from a business dispute over who had the right to conduct business in a certain area. And it would be a bit too callous to say that Tyrone ended up on the wrong end of that discussion. But here we are, now firmly situated in the emergency room, where Tyrone has been waiting for Dr. Wilson. Who, after a few hours, enters the patient room, closing the door behind him.

“What it do my brother!”, Tyrone exclaims with a forced sense of enthusiasm that appears artificial to Dr. Wilson.

“One of the techs mentioned that you would like to speak with me – I’m happy to talk, but I’m afraid I only have a few minutes to – ”

“Man why do you talk like them white folks”, Tyrone deliberately interrupts, contorting his face in a patronizing disgust to make the effects of his words seem more pronounced.

“They don’t care about you. You like OJ – once they run you out, you won’t be shit to them.”

Dr. Wilson is visibly shook but maintains his professional calm. Instinctively he finds an excuse to leave.

“Thank you for your time, sir”, he says preparing to exit, “I understand you are to have the bullets removed shortly. Good luck.” As Dr. Wilson turns his back to Tyrone to exit through the now opened door, Tyrone makes one last remark.

“What, they don’t let the brother do the actual work. I guess you’re just the face hanging on these banners, but you don’t run anything.”

With a silent nod, Dr. Wilson exits, leaving Tyron alone in the room waiting to have the bullets dislodged. Two hours later a technician walks into the room to prepare Tyrone for the procedure and carts him to the operating room.

I will spare you the details of the actual procedure itself, but there is one thing worth mentioning. Dr. Wilson was there, not operating, but overseeing the procedure. As the director of the trauma division, he oversees all surgical procedures, and was guiding the more junior physicians as they perform the actual procedure.

Which went as expected, with the operating team anticipating full recovery for Tyrone in two days. Which means Tyrone and Dr. Wilson will have another opportunity to meet, which takes place on the first post-operative day while Dr. Wilson is leading the clinical team on morning rounds. As they enter the room, the junior physician – the one who performed the procedure – begins to speak.

“Patient is hemodynamically stable and has urinated though no bowel movements yet. Wounds healing appropriately with no signs of infection.”

“Excellent”, Dr. Wilson responds, “how is his oral intake?”

“He has been cleared for thick liquids but, as far as we know, has had nothing to drink. Let me ask him if anything is bothering him.”

The junior resident places his hand tenderly on Tyrone’s shoulder gently nudging him to get his attention. Tyrone, unaccustomed to such gentleness widens his eyes and thrusts his shoulder away.

“Who is you man? Don’t touch up on me like that!”, Tyrone screams as he furrows his eyebrows in disgust, an expression Dr. Wilson recognizes.

“We’re the trauma team”, the junior physician responds calmly, “we removed the bullets and we want to monitor your healing. Sorry to bother you, but we have a quick question – did you drink anything yet?”

“Yes, been drinking and pissing water all day. Something more would be nice.”

“Got it”, the junior resident smiles as he makes eye contact with Dr. Wilson.

Dr. Wilson smiles back and in an unusually warm tone says, “let’s fix up a nice thick milkshake for our guest.”

At the sound of Dr. Wilson’s words, Tyrone fixes his eyes and regains his characteristic snarl, retorting, “if it ain’t my main man Wilson. They got your riding the dog and pony show, huh?”

The junior resident, alarmed at the lack of respect, both in the tone and the words, immediately interjects, “please don’t speak like that to our director, sir”, speaking with a practiced calmness typically reserved for correcting a young child’s manners.

Dr. Wilson returns to his stoic demeanor and extends his right arm loosely out and motions his downward facing hand up and down, beckoning a sense of calm among everybody in the room. With the same hand he then gestures the team to leave the room in silence.

Upon noticing the second gesture, Tyrone grows visibly irate, screaming, “you don’t run shit man – I’ll move my fist to your face.”

The junior physician recoils his head, taken aback, “are you threatening violence?”

“What do you care, white boy? This brother Wilson is just a face on a banner, a figure head, you the real man”, Tyrone grunts to the junior physician as he cocks his head to make direct eye contact with the junior physician.

The junior physician widens his mouth in shock, his eyes widening with emotion, and point his right index finger at Dr. Wilson, “I’ll have you know that Dr. Wilson taught me everything I know about trauma – he is the reason I am even here. Show him some respect.”

With that Tyrone grew silent and cocked his head in the other direction, turning away from everybody in the room, leaving Dr. Wilson to motion the team to leave the patient room in silence.

After a few steps down the hall, Dr. Wilson stops walking and looks down. The team stops in tandem, expecting Dr. Wilson to speak.

“You should not have done that”, Dr. Wilson says after a long moment’s pause, continuing to look down, not making eye contact with the junior physician – simply staring.

“Why? – of course I’m sorry – but why, why do you say that? He should not speak to you like that”, the junior physician responds, quivering with a palpable anxiety.

“Because he was not speaking to me, he was speaking to himself. What he sees in me, is the possibility of what he could have been, but did not become, for whatever reason. I form a reflection for him to see two sides of himself – one mirrored in reality, and the other an idealistic vision he holds for himself. And many times, when people see me, knowing that I am from this area, they compare their life trajectory with mine and create certain justifications about me to give themselves a sense of satisfaction – some transient upliftment. Let the patients have those moments.”

With that Dr. Wilson resumes his walking and the team joins him in stride, silently internalizing his words of wisdom in the few moments before they see the next patient on their morning rounds.

For Tyrone, those same moments last a bit longer, as he is left in silence with an invalid body that is slowly healing. But his focus is not on the scars on his body, but the scars in his mind, which appear through the expressions on his face. But not as the familiar grimace of disgust or anger we saw before. Rather, as a pained tight-lipped face with eyes staring blankly ahead, welling up and overflowing with tears, forming tributaries of tragedy as he reflects upon the course of his life.