Risk has always been relative.

When you have a little, you are willing to take great risks. When you have a lot, you are less willing to take risks. It has always been that way, from family game night to corporate strategy in the board rooms.

And is the policy of most medical device companies, which are surprisingly risk averse despite the rapid influx of innovation into healthcare over the past decade. Yet this incongruity explains why numerous medical device startups have flourished in recent years.

Most large medical device corporations do not want to take the risk of introducing new medical devices into the market. For these large corporations, research and development are effectively mergers and acquisitions. This is why the pandemic did little to effect startup investing and acquisitions in medical devices despite the slowing of patient visits and of device sales in general.

The economics of startup investing are separate from the economics of device sales. Intuitively this does not make much sense. We assume that a corporation would invest in a device to increase sales. But corporations do not think in terms of revenue alone. They weigh revenue to risk, and only pursue revenue when the risk has been reduced.

For new devices, though the potential revenue is great, so is the risk. And the ratio of revenue to risk is what determines how the corporations will act. But that very ratio defines the upside for new medical devices that lead so many to pursue innovations.

According to a 2020 publication by the consulting firm, the Boston Consulting Group, the ten largest medical device corporations only hold 40% of the market, or roughly 4% per corporation, with no one company owning more than 8% of the market revenue. This would imply that the market is fragmented and ripe for a startup to come in and capture market sales.

But healthcare has always been a niche industry, and market shares should be understood in terms of specific diseases or set of diseases. When viewed from that perspective, the market looks quite different. For example, in the orthopedics market, four corporations control 80% of the market. That is true market dominance. And for a small startup trying to build sales, it quickly becomes apparent that true sales comes through acquisitions.

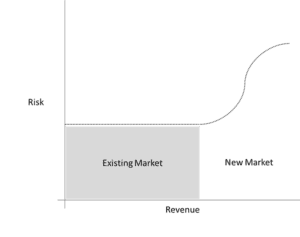

From this perspective we can begin to see the disparity between the sales market and the innovations market for medical devices. As seen in the figure below, large medical device corporations focus on existing markets and optimize sales when risk is low. New markets, in which novel medical devices can enter, have a higher risk, which most large companies do not enter, leaving open an opportunity for startups. Once a startup has proven that the unique device can generate sales, they will acquire it.

The ability to generate sales reduces the risk of the device, and, subsequent to sales, the device transitions from the new market to the existing market, enjoying a long, low-risk life of recurrent sales through the behemoth sales network most large medical device corporations enjoy.

They create value through scale, and the larger they become, the greater scale they create. Scale defined by low-cost sales and by mitigating all possible risk.

The focus of the two markets is diametrically opposite and explains why new markets are thriving with innumerable startup companies and why existing markets are thriving with large corporations that enjoy significant market shares within their specific market segment.

This balance is firmly entrenched in the minds of many medical device entrepreneurs who prioritize building technologies with robust intellectual property protection to maximize the value of medical devices once they become ready for market sales. Most do not even consider the prospects of selling devices and pitch early, quick investment exits to investors when raising startup capital. Investors, who are well aware of the potential for quick returns through this balance, continue to happily invest in new medical devices knowing the acquisition market will remain strong for devices who demonstrate a potential for sales.

Yet even in the dynamic world of startups there is room for disruptions.

Not by disrupting the development process for medical devices, but by disrupting the balance between startup companies and large medical device corporations – and connecting new devices directly with the end user, the patients.

This would be a business model innovation changing very approach to device sales. And the startup that can figure out how to disrupt the sales process can reap significant rewards beyond traditional returns gleaned from an acquisition.

If there ever was a time to attempt this disruption, it would be now.

Hospitals and large healthcare systems saw how quickly their finances depleted during the pandemic. Most hospitals optimize their operations through low cash reserves, as a means of increasing profit, but a strategy that left many scrambling for financial aid at the most inopportune time, early in the pandemic. Only through government support and subsidies for medical equipment were many hospitals able to make it through the pandemic. They remember the financial risk they endured, and they, like medical device corporations, will mitigate against all possible risk.

Which includes the risk of purchasing medical devices, a major financial burden hospitals are loathe to take, even for essential medical equipment and supplies.

Normally hospitals purchase devices with significant markups because medical device companies invest large capital into the sales process, and happily pass those costs onto the hospitals buying the device. This creates a large upfront cost on hospitals.

A startup that can reinvent the sales process by focusing less on mark-ups, and more on the clinical utility of the device being sold will find a very eager hospital market. Instead of selling a device at a fixed price, a startup would sell the device at a price relative to the cost savings enjoyed by the hospital in using the device for patient care. Of course the smaller startups will have to find hospitals willing to purchase devices directly from them, which is no small task.

But the model is elegantly simple. Instead of buying devices at a fixed cost, hospitals would pay for the device based on how frequently it is used and how it is used. The cost of care would be benchmarked to a national database on cost per patient or per clinical condition. Whatever cost savings or additional financial benefits the hospital garners would be passed along to the medical device company as the adjusted the cost of the device.

Effectively creating a sales model based upon clinical gain-sharing.

The margins saved by hospitals would be immense, and the startup that can prove itself credible in the eyes of hospital administrators and provide devices through this unique payment model would rapidly capture market shares.

This new sales model shifts upfront fixed costs to ongoing variable costs that the hospital incurs based upon the utilization of the device. But it is different from commission or consignment models because the cost incurred to the hospital is based upon the clinical impact, not a fixed price.

So hospitals pay only when they use the device, and the cost of the device is directly related to the relative value the device provides when used to care for patients.

By equating clinical impact with hospital expenditure, hospitals can avoid excess premiums seen in traditional sales models for devices. Larger corporations will naturally be hesitant to this adopt this model of care because it would erode their existing profit margins.

This is where startups can truly shine. With no legacy overhead or existing profit margins to benchmark from, startups can implement this new disruptive model of sales until this disruption become the standard sales model.

An opportunity only a startup can truly obtain.

And why medical devices are truly for the startups.