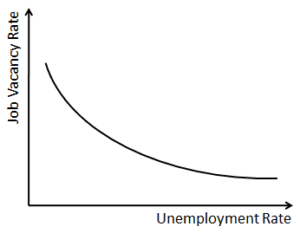

Economists who study labor markets use the Beveridge Curve to make sense out of trends they see. The curve is a graph of the relationship between unemployment and job vacancy, the number of unfilled jobs expressed as a proportion of the total available labor.

The graph has vacancies on the vertical axis (y-axis) and unemployment on the horizontal axis (x-axis). The curve slopes downward and approaches the axes asymptotically at extreme values, indicating high unemployment comes with low vacancies and low unemployment comes with high vacancies.

This may be true for the labor market as a whole, but it certainly does not reflect the current reality of employment in healthcare. Health policy wonks would have you believe healthcare has a problem with access to care – that those who need health services struggle to get it because they do not have access to the right healthcare providers.

This implies healthcare has a high number of job vacancies. But we also hear pundits lament high employee turnover and burnout in healthcare, which implies conversely that healthcare has high unemployment rates.

Which one is it then? High vacancies, high unemployment, or perhaps both?

Here we begin to see the complexity of the healthcare labor market. We like to distinguish between highly skilled professionals, like physicians, and those with less formal training, like registered nurses or the various technicians who fulfill the clinical orders, who actually execute clinical care.

In reality, the two labor markets are one and the same. A physician cannot care for patients without an army of medical assistants. A phlebotomist cannot draw blood without knowing which orders to carry out. In no industry do we see such interdependence between a highly trained, highly skilled workforce, and those considered otherwise.

But we insist on creating artificial distinctions in the labor market, and monitor each job position in healthcare as its own trend. In creating unnatural distinctions in the labor market, we produce unrealistic findings in healthcare labor trends.

The match, the name of the system where graduating medical students find out where they will train for residency, continues to celebrate ever growing numbers of residents matching into various clinical specialties. This gives the impression that the labor market for physicians is growing.

However, a closer inspection would indicate otherwise. The same 2022 match, which boasted the highest number of medical students matching ever, also had the highest number of vacancies in the field of emergency medicine. In glossing over these concerning findings, we are left to believe in overly optimistic outlooks on job growth that may never materialize. The reality is that there are growing disparities in the clinical specialties medical students choose to enter.

And as physicians in training quickly realize, they cannot practice medicine without the support of nurses, who are leaving clinical medicine in droves. Nearly one third of all nurses intend to quit working or transition to non-clinical roles by the end of 2022.

The reasons for this remain murky. Nurses cited burnout and high-stress work environments as the main reasons for leaving. But among those who have left or are in the process of leaving, higher salaries are the top motivating factor for taking non-clinical positions. This means the reasons for leaving a clinical job are different from the motivations for accepting a non-clinical job.

Nurses are not alone in this exodus. A survey released by Elsevier Health, called “Clinician of the Future,” predicts that up to 75 percent of all healthcare workers will be leaving the healthcare profession by 2025.

But the Beveridge Curve says that job vacancies and unemployment are inversely related. We cannot have both – high vacancies and unemployment – unless the labor market is undergoing a structural shift, which is exactly what the healthcare labor market is going through.

As it currently stands, there is no one labor curve in healthcare. It is a series of disjointed jumps and slopes that form something we do not yet fully understand.

Yes, healthcare struggles with issues of access. But access means more than availability or simply providing care. Access means optimizing the labor market by balancing the employment of everyone who works in healthcare, from physicians to nurses, and from transporters to technicians. This is the real labor market, and it is high time we study it with the rigor it requires.

If indeed the number of resident physicians is growing, then what do we make of the decreasing number of nurses? If the trends continue as broadcasted, then we will have a surplus of physicians and a shortage of nurses. The ability to provide effective care – the ultimate purpose of the healthcare labor market – will be constrained accordingly by the number of nurses.

Healthcare labor, therefore, should not be characterized by trends in individual jobs, but in ratios of various clinical providers and downstream workers. An ideal labor market optimizes the ratio of physicians to nurses to technicians, and onward. The interdependence is effectively the labor, as that is what forms patient care.

Fortunately, we have the data to map these ratios. We know what healthcare jobs are trending across the country. But we kept the data distinct, isolated to individual professions. Now we must integrate the data to glean trends that may not appear obvious, but will prove consequential in predicting which trends are meaningful and which are hollow forecasts.

While we may not yet understand the trends that will materialize in the healthcare labor market, we must acknowledge that the issue goes beyond calls for increasing access to care. Until we map these structural shifts properly, as ratios of employment, we will not know the implications of these supposed trends. The labor market is shifting, and the best way to recognize these shifts, and its ensuing impact, is to study the ratios.

So we can see healthcare labor as it actually appears in patient care.