The patient encounter, the heart of healthcare, is unique in its speed and complexity, unlike any other setting found in society: patients discussing the most vulnerable and intimate aspects of their lives and providers analyzing the experience while extracting clinical knowledge – which together form the patient narrative.

Ultimately, our entire perception of healthcare is understood through the process of storytelling. And the clinical experiences we go through dictate the story we tell ourselves and others about our health.

When two people speak normally, the thought patterns driving both the verbal and nonverbal forms of communication are balanced, or symmetrical. Whether it is two friends meeting at home, two workers at the office, or any other traditional setting for conversation, we assume most conversations to be on an equal footing.

In contrast, the clinical encounter is asymmetric from the onset, as every encounter is between someone who is a perceived expert, and someone else who is not. The word “perceived” is important. An expert, says behavioral economist Daniel Kahneman, is someone who has studied something in depth, and developed more associations, or a greater number of intersecting thought patterns, than a non-expert. The expert in healthcare, the clinical provider who has studied medicine, understands the relationship between symptoms, physical findings, and clinical data in greater depth than the patient does. But learning something in detail also influences how someone thinks, which then creates thought patterns unique to the provider that in turn form its own heuristic.

As a result, a dichotomy forms between provider and patient. The provider perceives the presenting symptoms of the patient in the context of clinical knowledge previously obtained. The patient perceives the presenting symptoms as a direct personal experience. The exchange of information is asymmetric, because the frames of reference are different.

The expert may have a better understanding of clinical medicine, but that does not equate to an absolute understanding of every presenting clinical condition. Recognizing something in greater detail does not mean that a person automatically recognizes it with greater accuracy. Yet we find ourselves drawn in by expert views and often accept them without question, largely because we confuse more knowledge with more accurate knowledge. But just because you’re closer to the target doesn’t mean you hit it. Conflating the heightened marksmanship of an expert with absolute truth simplifies an otherwise complex conversation about a person’s health.

If your blood sugar is high, it is much easier to hear that a medication once a day can control your blood sugar than to delve into a discussion about uncertain relationships among stress, behavioral changes, and family histories. But these very uncertainties dictate the patient’s response to the medication.

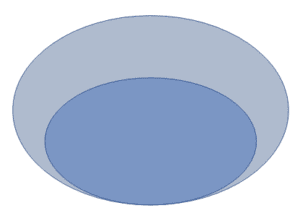

The graph shows the relationship between information given and the response taken, with two circles representing a known response and an unknown response. The known response (dark shading) is our conscious reactions. The unknown response (light shading) is the more subtle, unconscious manifestations that we are not aware of but that we are impacted by – the “I did that?” moments. Notice how the perceived expert, with greater associations of facts and data, still struggles with uncertainty, albeit less uncertainty, than a perceived non-expert.

Both providers and patients see the same uncertainty during any patient encounter, but the response to the uncertainty is what separates the provider from the patient. A provider will rely on more clinical information, more association patterns, to address a greater portion of the uncertainty. But neither the provider nor the patient can address it all. Presuming what is known to be all there is to know ignores the underlying uncertainty present in every patient encounter. This bias, common in healthcare, is called the narrative heuristic. Since we abhor uncertainty, we will simplify and modify any complex concept into a comfortable, convenient narrative, however incorrect: disease and pill, problem and solution.

As a result, most providers would rather adhere to guidelines and protocols that define the standards of clinical care. Because providers are formally educated in clinical medicine, they train their minds to revert to what they know and have studied. It simplifies the patient encounter, but it introduces biases in the process. But medical knowledge is an oasis of knowledge within a desert of uncertainty, and a clinical encounter is nothing more than an excerpt from an ongoing story that we are not even aware of, and only learn about after they are well underway.