Even those who nominally follow particle physics have heard of the Higgs boson particle, the famed god particle.

But the famous particle is not a traditional particle as we understand it, more of an interaction. Physicists often use the analogy of pouring water into a bucket to explain the Higgs boson particle – defining it not as the bucket, nor the pouring water, but the splash that forms when the water comes into contact with the bucket.

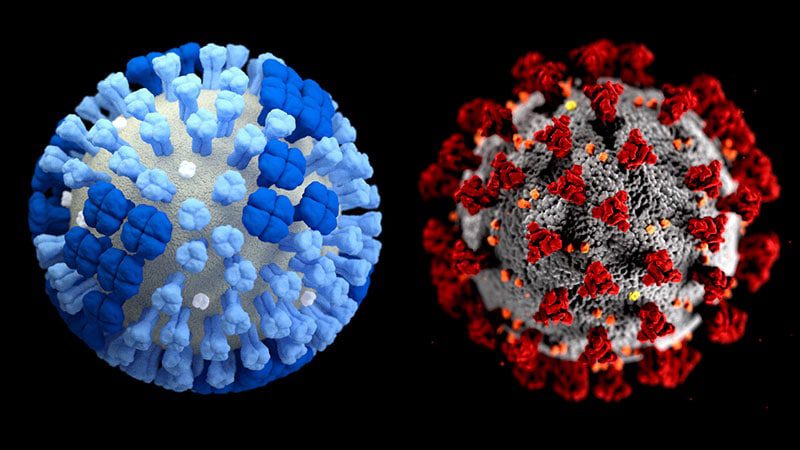

Physicists understand the Higgs boson particle is best explained as an interaction. An analogy that is also useful to explain why we have not seen more cases of the traditional flu – influenza – during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Australia, the country from which we derive our annual influenza predictions, had historically low influenza cases in 2020 and continues to remain at historically low levels in 2021. In the United States, we predict the severity of the flu season and develop annual influenza vaccine formularies based on the number of cases and type of influenza variants seen in Australia, during its flu season earlier in the year.

In late August, the Australian Department of Health issued the following statement on its website:

“Given the low number of laboratory-confirmed influenza notifications, low community [influenza-like] activity, and no hospitalizations due to influenza at sentinel hospital sites, it is likely there is minimal impact on society due to influenza in 2021 to date.”

The statement bodes well for the United States as we enter our flu season.

The CDC monitors domestic influenza virus activity and publishes its results through an Influenza Surveillance Report updated weekly. As of the end of August, it reports minimal to low influenza or influenza-like activity throughout the country, save for New Mexico and Georgia.

Findings consistent with what is being reported in Australia, save for the following statement:

“In addition, health care-seeking behaviors have changed dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many people are accessing the health care system in alternative settings, which may or may not be captured as a part of [our dataset].”

The surveillance reports, which contain multiple datasets ranking influenza viral severity from very high to minimal, now include large sections of insufficient data since the start of the pandemic.

As a result, there is much we cannot predict as confidently as we could have during non-pandemic years. And when there is uncertainty, there is inevitably mass speculation.

Journalists are already predicting the 2021 flu season will be far more severe than normal, despite no data to suggest this. And publicity-hungry physicians and policy experts are all too eager to corroborate these specious claims.

Those making these claims have no data to support their position. They are simply using conjecture and inductive logic to justify their stance. Since we will have more interactions – either due to COVID-19 vaccinations, or pandemic fatigue, or return to work orders – we will have less masking and social distancing. Therefore, influenza will be more severe than in previous years.

The logic is absurd. But who needs logic when you have catch-phrases like “twindemic”?

Now we have media outlets advocating for yet another vaccine on the basis of conjecture alone, further alienating the public and eroding trust in public health policies.

We love to indulge simplified narratives, but we should follow the data instead.

In September 2020, the CDC issued a report predicting that year’s influenza activity and its public policy implications. The study concluded – correctly – that influenza cases in 2020 will be less prevalent than in previous years, attributing the cause to fundamental viral behavior:

“Like SARS-CoV-2, influenza viruses are spread primarily by droplet transmission; the lower transmissibility of seasonal influenza virus (R0 = 1.28) compared with that of SARS-CoV-2 (R0 = 2–3.5) likely contributed to a more substantial interruption in influenza transmission.”

Simply put, influenza does not spread as effectively as COVID-19. And like two competing predators in the same ecosystem, the more effective predator wins out.

We have known for over a century that viruses have their own global ecosystem, called a virosphere. But it may still surprise the public to know that viruses are among the most abundant and diverse organisms, hiding in plain sight within their own global virus-host network.

Unlike other organisms that we understand as individual species, viruses are best understood as an interaction. Each virus has a partnering host that it interacts with, and that virus-host interaction defines the virus.

When COVID-19 enters a human host, it spreads more rapidly than when influenza enters a human. Over time, the more rapid spread leads to a greater prevalence of COVID-19 than influenza.

Since both COVID-19 and influenza have the same host, they are essentially in competition. And like two competing predators, only one can win.

Therefore, as COVID-19 and its variants continue to infect us domestically and around the world, it is more reasonable to expect that influenza rates will remain low. Competition within an ecosystem is an opportunity-cost. If one wins, then the other must lose.

At the beginning of September about 160,000 Americans tested positive for COVID-19 daily, a 14% increase over the last two weeks of August. As the variants continue to evolve, we can expect more COVID-19 cases – and less influenza cases – in the coming months.

This also means we can expect more speculative logic and conjectures as well – both of which are a part of our daily interactions with the pandemic.