“No one realized an epidemic was going on”, an anonymous Chinese patient reported in early 2020 at the onset of the COVID-19 in China.

That was just one patient’s words. But it could have been any one, as most of us were in some way caught off guard by the pandemic.

The tendency to continually be surprised by new trends in healthcare is the well-known familiarity bias that we have seen before, whether we have recognized it or not.

When presented with a new set of symptoms or a new disease presentation, we initially seek to understand it in familiar terms. Our biases always prioritize the familiar, which means our interpretations come from a frame of reference that assumes we have seen this before.

And we rely on our initial interpretations to set the framework for how we interpret new information, and subsequently understand it further. Hence the power of initial impressions.

Only when we have added enough unique perspectives, do we adjust our frame of reference through interpretations that acknowledge the uncertainty. With every new perspective, be it a direct observation, an experience, information received, we add to the frame of reference. Which accumulate into one aggregated set of perspectives, that determine the dominant perception through which we interpret something new or unfamiliar.

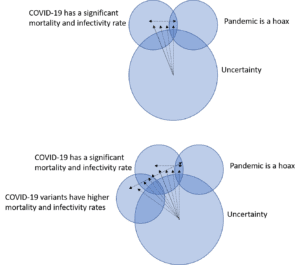

When we first heard of COVID-19 variants, we were not sure how to understand them. For many still coming to terms with the pandemic as a real disease, it takes yet another shift in perception for those to understand and become consciously aware of the heightened risks the variants pose. Take for example, a person who initially struggles to understand the pandemic.

When she first hears about the variants, she processes the new information from the perception she currently has. She consciously interprets the variants to be more dangerous only after she has sufficient reasons to change her perception. As the new perspectives accumulate and influence her overall interpretations.

This shift occurs differently among different people. For those familiar with virus mutations and epidemics, it may not take much to shift perceptions. For those struggling to understand whether the pandemic is real, this shift may require more information and more time. It depends on how the person understands new information, and the existing perceptions the person holds. All of which predispose the person to first look in terms of what is already familiar, reinforcing the heuristics emanating from familiarity biases.

To think about something new requires us to first understand what makes it new. That comes from understanding the uncertainty through which we are deriving our thoughts. We naturally assume something that is new relative to things we already know or are familiar with.

But only after we shift our frame of reference do we actively entertain the possibility that we are observing something new. We overcome familiarity biases by focusing on the uncertainty that gives rise to the heuristic.

The easiest way to do this is by refocusing our attention on thoughts opposite to our dominant perception. If we believe we should order a test, we should also consider why we should not order a test. Emphasize the opposite whenever interpretations are leading to a decision. And once both the predominant perception and its opposite have been considered, visualize the corresponding decision that arises from interpretations of either perception. Determine what makes one decision a better option compared to its opposite.

That consideration, and subsequent determination, creates awareness.

Awareness changes the way we approach every decision. Instead of deciding upon something and reflexively acting, we are balancing options relative to one another. Healthcare decisions then become the clinical equivalents of opportunity cost decision-making.

As the decision to order a lab is no longer an instinctive order, but a balanced consideration to order or not, integrating all the factors that go into that decision – cost, medical need, unnecessary punctures to the patient – each weighed accordingly.

Great chess players look at a chess board and see both the pieces and empty spaces. Great clinical decision-makers look at any decision in terms of what is known and unknown, and of relative benefit and cost. Fully aware of all the factors that go into every decision.

Without structuring clinical decision-making, most interpretations are generated reflexively. Often by adhering to a set protocol. Or generated chaotically. By listening to the fluctuating perceptions of the moment.

Lacking structure, different factors are considered more important compared to others, and what we consider important is typically a reaction to something we encountered recently.

A provider who missed diagnosing a patient with anemia will thereafter order hemoglobin blood tests on more patients, and with greater frequency as a reaction to the one decision not to order a hemoglobin test.

Establishing a structured frame of reference addresses this tendency to react. Allowing providers to interpret new information without reacting to previous perceptions, and to understand the current uncertainty presenting in the patient. A shift in thinking that leads to better decision-making.

Something Dr. William Osler advocated when emphasizing bedside learning for medical students initially learning how to evaluate patients. He believed that maximizing direct experiences with patients will lead to better quality of care. Not because we will glean new data or uncover something previously hidden through such efforts, but because direct experiences with each patient allows us to understand the patient better.

Developing a more accurate assessment of how the patient thinks, and how the patient internalizes the care received. Which allows providers to make better decisions in turn. Better decisions derive from more accurate perceptions that come only through time and direct experience with the patient.

Many may argue that it is not necessary to think this way most of the time. As most of medicine is based upon recognizing a familiar constellation of symptoms and signs, and diagnosing and treating patients accordingly.

Over time, providers associate certain symptoms and signs with a specific diagnosis or treatment. And this process eventually becomes a thought pattern that is mechanically observed, situation after situation. In which the provider first notices things that are familiar and then gradually begins to become aware of differences afterwards. Since our minds think this way, our decisions are made in this way.

Which explains why much of the care for cancer patients focuses on treatment protocols after the cancer has already been formed, and less on optimizing the early detection of the first symptoms. Early detection requires a shift in awareness to interpret the early symptoms differently.

In a way that optimizes the way we approach the uncertainty around an initial set of vague symptoms. Cancer researchers who study early detection find the proper interpretation of the symptoms is as important as the symptoms themselves.

Optimizing clinical decision-making does not come down to fixing a set of perceptions or interpretations. That simply produces more familiarity biases.

Rather, it depends on being aware of how the different perceptions fluctuate to create different interpretations. Become aware of the biases to preemptively address them.

Instead, we attempt to standardize clinical care by creating set thought patterns that fix the way we think. Reinforcing heuristics without being consciously aware of it. In dynamic, chaotic ways largely without us knowing.

But in the process of structuring these patterns, we fix the interactions that define healthcare.

Whether it is between the provider and patient, patients and their thoughts, or the dominant perception and its subsequent interpretation.

To what is familiar, and what is not.