In 1967 former surgeon general Dr. William Stewart declared the first of many figurative wars in healthcare. He galvanized the medical community by inciting a war against infectious diseases. And mounting a campaign to eradicate all infectious diseases through the aggressive use of antibiotics.

He allegedly declared the war won in just two years.

Flash forward roughly a half-century later and we see the lingering effects of this war: seven hundred thousand deaths in 2019 due to antibiotic resistant infections; eighty-eight million antibiotics prescribed from 2004 to 2013 without a patient encounter; and drug development for novel antibiotics basically nonexistent as the only companies willing to develop new antibiotics are startup companies. Since large pharmaceutical companies have refocused their development efforts towards clinical conditions perceived to have higher financial upsides.

Did we actually win this war?

An inherently nonsensical question because healthcare is not a war to win, but a balance to attain. A balance that requires us to accept what we do not know and embrace the uncertainty in treating infectious diseases.

Healthcare is filled with such balances, found in nearly all diseases. We generally believe sickle cell disease arose as a response to malaria exposure, offering those with the specific sickle-cell blood type protection against the disease at the cost of suffering from the blood disorder.

But this type of balance is not unique to just one disease. They are more common than it would initially appear. A lesser-known relationship is believed to exist between inflammatory bowel diseases and parasite exposure, particularly the parasite, Trichinella. And when many diseases and the corresponding immunological responses are examined closely, we often find an innate balance that governs the interaction.

Many biologists believe we disrupted this balance when we eliminated the exposure to pathogens, such as natural bacteria and parasites, our bodies had grown accustomed to in our quest to build hygienic living conditions. And by upsetting the balance between pathogen exposure and immune response, we gave rise to autoimmune conditions that were previously uncommon.

But this relationship is more complex than directly equating pathogen exposure with immune responses. As most studies which attempt to attribute one specific cause to an inappropriate immune response fail to demonstrate any meaningful cause and effect relationship.

The true balance comes from all the immune triggers and responses weighed together. Which we have yet to decipher. Leaving us to try and make sense out of incomplete interpretations of relationships that are complex and correlative.

There is more we do not know than do know when it comes to our immune responses. Even the traditionally held belief that pathogens are generally bad for us is proving not to be true. It has been estimated that up to 8% of our genes are viral in origin, and many of the proteins in our body behave like some of the deadliest viruses in the world.

Making the study of uncertainty within our immune systems the key to understanding the balance of factors guiding the behavior of our immune systems.

And any misguided, extreme attempt to disrupt this balance, be it eradicating germs with antibiotics, or eliminating natural bacteria through excessive hygiene, always produces reverberations with effects that run counter to the original intentions.

Demonstrating how healthcare behaves dialectically, shifting from one response to its opposite.

Whether we are in the world of infectious diseases or the world of clinical perceptions and interpretations.

With the same fluctuating thought patterns that regulate the way we think also shaping the way we communicate. As both behave according to dialectic principles that routinely influence one another, shifting back and forth.

And explain the cascade of perceptions and reactions we observe in law and in health policy, with each becoming more extreme than the last. Something we first saw during the opioid epidemic.

First there was the emphasis on the treatment of pain, until the management of pain became the focus of care. Then came the narratives of lives lost and families disintegrated by the abuse of opioids, heroin, and fentanyl. Which was followed by the onslaught of aggressive government intervention and reaction. Leading to another set of narratives in which all sides attributed blame at will, prompting even more extreme reactions.

On it went, cascading in a dialectic progression in which mythos, or emotion, becomes valued over logos, or reason, until mythos became logos. Or until the extreme emotions become the basis for our perceptions.

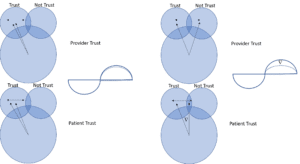

That we can see in the perceptions that form and can model through diagrams. When we create our own perceptions, we tend to reinforce beliefs we currently hold. We rarely come across a situation in which we change our own beliefs on our own accord.

When we encounter others who share beliefs similar to the ones we hold, we inevitably become more extreme in our own beliefs. This is because we gravitate towards beliefs that only reinforce our own views instead of incorporating beliefs that both reinforce and refute what we believe. As a result, we create selective echo chambers in our minds, constantly emphasizing what we already believe while ignoring what contradicts what we believe.

The more news and information we incorporate, the more self-reinforcing perceptions we receive. With each additional perception received, the overall interpretation becomes more extreme. Since we selectively integrate perceptions that align with our preexisting interpretations.

As the opioid epidemic became headline news, the perceptions of the epidemic became more extreme. Exactly through this process of selectively integrating perceptions that reinforce more extreme interpretations.

With reverberations felt in patient encounters across the country in the same dialectical progression.

Since the way we communicate affects the way we think, the guidelines providers reference when prescribing opioids dictate their decisions to prescribe. With the interactions between the guidelines and the providers largely influencing the behavior exhibited.

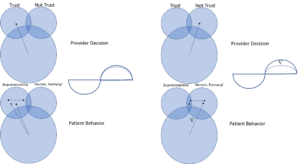

Ideally such guidelines should balance the need for opioid medications with the underlying risk of opioid abuse. But the uncertainty in applying the guidelines to specific patients prompts reactions from providers which are responsible for the dominant perceptions dictating the decisions to prescribe.

Generating interpretations that lead to further reactions by patients. That in aggregate predict the substitution patterns observed among patients. Who subsequently respond to the uncertainty of not knowing whether they can continue to receive medically necessary pain medications.

In the diagram we see the following perception shifts among different providers, and the commensurate shifts they prompt among patients. In the scenario on the left the provider trusts the patient. The patient recognizes the trust and maintains compliance with opioid medications.

In the scenario on the right, the provider begins to distrust the patient. To which the patient begins to recognize the distrust. The diverging thought patterns mirror the change in perceptions that grow as the trust between the provider and patient erodes.

The diverging thought patterns lead to further shifts in patient perceptions that have additional, lasting consequences. Suppose the provider distrusts the patient because the provider believes the patient is developing dependencies to the opioid medications. If the provider does not trust the patient, the provider may not consider opioid abuse medications, and instead simply discontinue seeing the patient.

Which may influence whether the patient transitions from opioids to fentanyl or heroin, instead of to medications such as buprenorphine, which have proven to help patients manage substance use dependencies. The provider’s perception of trust impacts the patient’s subsequent behavior, which can turn patients with nascent addictions into outright addicts, or vice versa.

The quality of communication directly impacts the quality of care. With the perceptions derived over the course of a patient encounter directly influencing the ensuing patient behavior.

Which means healthcare is not a battle against a figurative enemy or disease – whether it is the war on infectious diseases or the opioid epidemic.

It is a balance we need to attain among our very own perceptions.