Uncertainties appear differently in the moment and after the fact, retrospectively. And the differences in the perspectives helps us understand how to approach future, similar uncertainties. Which is really the basis of medicine. Medical students are taught to make clinical decisions parsing clinical information one after another, symptom after symptom. This is an uncertainty minimization framework. Which we standardize in healthcare to simplify patient care by deriving similarities in one clinical presentation to another.

But healthcare is inevitably dynamic, and uncertainty will almost never appear exactly the same twice, leaving us to approximate what appears similar and what appears different – relying on a system of judgement that is uniquely different for everybody.

Which sounds easy enough, but, healthcare is complex – meaning it is dynamic and ever-changing – so the biggest challenge comes from building a framework of judgment that is consistent across the various ways of thinking. Easier said than done, as healthcare gets exceedingly complex, very quickly – even in the most mundane of clinical scenarios.

If a patient takes one medication, you manage patient compliance, progression of the disease, and potential side effects of the medication. If a patient takes five medications, you have to worry about compliance with each medication, progression of each of the diseases, and side effects of the medication, not just with the patient, but with each of the other medications as well.

But law is, by nature standard, or simple. We know what laws to follow, what to do and what not to do, precisely because of the simplicity of the law. But when we make healthcare laws, we are attempting to simplify a complex concept. And in attempting to fit a fundamentally complex concept into something far more simple, we inevitably find errors of approximation – that manifest in the court of law as inductive logic, probabilistic and circular reasoning, fraud, and suppressed premises – errors that for many facing the legal ire of the law during the opioid epidemic produce maliciously harmful interpretations of law that violate their civil liberties and natural rights.

A recent study on co-prescribing opioids with anxiety medications, specifically benzodiazepines, found that a third of all the providers in the study prescribed anxiety medications for back pain: implying the physicians were prescribing anxiety medications outside its intended scope, using benzodiazepines to wean patients off opioids, or recognizing that pain and anxiety are closely related, and in the patient’s mind, different presentations of the same underlying condition.

The likely reasons among all the providers are probably some combination of all three, but the perception of your response dictates your response. If you believe the providers are prescribing outside of the scope, then you would believe legal action is warranted, but if you believe the providers are attempting to wean patients off opioids or treat the anxiety that stems from back pain, then you would work to ensure proper oversight is taken to avoid medication abuse or dependencies, believing the treatment to be inherently medical in nature.

When you are not certain which interpretation fits which individual provider, you base your interpretations upon the aggregated behavior of all the providers together – and determine the similarities and differences in the individual provider’s behavior accordingly. But attributing those interpretations to specific individuals can often lead to erroneous assumptions. So rather than attempt to fit an existing interpretation to something, as current healthcare laws attempt to do, we should restructure our understanding of law – down to the core essence of medical jurisprudence – and study the underlying uncertainty to see what similarities and differences are present relative to previous cases of uncertainty you may have seen before – and structure the thinking of law and healthcare through a framework of uncertainty.

The vaping epidemic is a great example of analyzing the underlying uncertainty to make sense out of an initial set of confusing and incongruent data. At first the vaping epidemic was perceived to be a complex, mysterious epidemic, and only later we come to find that it was really two unique trends superimposed onto one another.

But these mistakes affect how we think, and affect our approach to healthcare. Lung cancer has long been attributed to smoking, a relationship studied far more than most relationships in healthcare. But a recent study found an increasing incidence of lung cancer among women that is higher than the rate of increase among women smoking. The study found 15% of lung cancer occurs in non-smokers, both men and women, but occurs among 24% of non-smokers who are women, indicating the direct correlation between smoking and lung cancer may be an incomplete explanation for lung cancer incidence.

Which makes sense, because statistics that attempt to correlate a complex set of behaviors to a particular clinical decision are inevitably incomplete, and often invalid – and most explanations of such statistics are filled with its own set of interpretations. A problem that reappears when applying poorly constructed healthcare laws, distilling medical behavior into statistics and measurements, from the legal world into the medical world.

But some would say this is the basics of healthcare insurance. A concept that began with the idea that cost sharing reduces unnecessary care, but the way the insurances are currently constructed, with a mandatory deductible, actually cause more harm than good by influencing when patients receive their medical care or if the care is worth the deductible payment. Introducing another element into the decision-making that may affect the overall behavior.

This issue became particularly pronounced when a slew of high deductible insurance policies under the Affordable Care Act made it prohibitively expensive to even use the insurance, even after paying the monthly coverage – to the point that many chose not to even use the insurance even though they purchased it. Deductibles were intended to prevent unnecessary use of medical care with the assumption that patients would default to using their insurance when need be.

But if the structure of the deductibles incentivizes the opposite behavior, to not use the insurance, then perception and subsequently, the purpose of deductibles changes. As a result, the original legal mandate of the law is now invalid.

When faced with this exact problem, ACA plans from Illinois instead implemented a default enrollment policy in which patients would automatically sign up for an insurance plan whether they intended to select the plan or not – altering the decision-making away from selecting an insurance plan to deciding when it is worth using the prohibitively expensive insurance given – changing how patients perceive their insurance plan.

The ACA plans in Illinois assumed the automatic default enrollment would simplify the process of obtaining and using an insurance plan, but simply changed the behavior of patients in regard to their insurance plan, an unintended effect of oversimplifying a complex behavior.

A mistake repeated in Arkansas when the state attempted to implement work requirements for patients to be eligible for the state’s Medicaid plans. A well-intentioned plan, but one that created two layers of hurdles – the first being the job requirement and the second being the appropriate reporting of the job requirement – the second hurdle being a surprisingly bigger deterrent than the first for many considering enrollment. Many hardworking independent contractors in Arkansas found themselves without any healthcare insurance because they did not complete the job reporting requirements to the satisfaction of state officials – demonstrating an undue burden imposed by the law on small employers and independent workers.

Healthcare laws are only effective if the intention of the law accurately represents the full breadth of the behavior it intends to address, and healthcare insurance laws are only effective when the intended use matches the behavior of the patient using it. Laws are rules formalized to direct an intended behavior, but when a simple law approximates complex behavior, the inadvertent consequences of that complex behavior determines the interpretations of the policies – producing a host of unintended effects.

Dr. Rana Awdish calls this the principle of dual effect, in that any healthcare decision has both a positive and a negative effect. Which we fail to understand fully, because the two effects – positive and negative – are not mutually exclusive, and the relationship between the two effects is as important as the effects themselves. The relationship between a healthcare law, and the underlying behavior – when taking into account all the potential behavioral responses – forms a natural paradox.

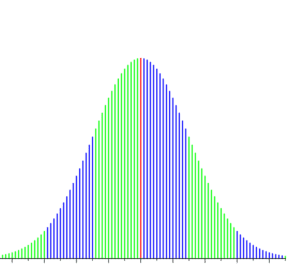

The graph below depicts how these paradoxes form. You see a normal bell curve, representing patient behavior, and the vertical lines superimposed characterizing the behavior incentivized by a law – and the width between the lines are called granularity deltas. The bell curve represents complex patient behavior, and the vertical lines represent the behavioral response to the law. The wider the lines, the larger the granularity deltas, and the more uncertainty arises in the behavior.

But uncertainty is not uniform across the curve. Patient behavior at one end of the curve is different relative to the other end, as a healthy patient does not make the same dietary decisions as an obese patient predisposed to stress eating. At any point along the bell curve, you will encounter a subset of patients who behave similarly and will respond in a commensurately similar manner. Each subset will then respond to the law in a predictable way.

The interaction between the patient’s behavior and the law can be traced along the bell curve, and the predictable response is a function of where you are on the curve (in reference to the likely behavioral response) relative to the distance from the vertical line (in reference to the law).

Ideally, the deltas should be zero, but realistically, the goal should be to minimize the size of the deltas to minimize the uncertainties characterizing the behavior relative to the intended effect. That should be the definition of a Constitutional healthcare law.

And should serve as the basis of medical jurisprudence for all healthcare law – and hopefully the method through which the Supreme Court analyzes the Affordable Care Act.

While this graph is entirely conceptual, it provides a critical framework to understand the interactions between an intended effect, and the interpretation of the intended effect, forming the crux of the legal interpretations for the Supreme Court.

Great blog you’ve got here.. It’s hard to find quality writing like yours these days. I honestly appreciate people like you! Take care!!