In a call with a long-time source, what stood out most to STAT reporters Bob Herman and Casey Ross was just how viscerally frustrated and angry the source was about an algorithm used by insurance companies to decide how long patients should stay in a nursing home or rehab facility before being sent home.

“The level of anger and discontent was a real signal here,” says Ross, STAT’s national technology correspondent. “The other part of it was a total lack of transparency” on how the algorithm worked.

The reporters’ monthslong investigation would result in a four-part series revealing that health insurance companies, including UnitedHealth Group, the nation’s largest health insurer, used a flawed computer algorithm and secret internal rules to improperly deny or limit rehab care for seriously ill older and disabled patients, overriding the advice of their own doctors. The investigation also showed that the federal government had failed to rein in those artificial-intelligence-fueled practices.

The STAT stories had a far-reaching impact:

- The U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs took a rare step of launching a formal investigation into the use of algorithms by the country’s three largest Medicare Advantage insurers.

- Thirty-two House members urged the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to increase the oversight of algorithms that health insurers use to make coverage decisions.

- In a rare step, CMS launched its own investigation into UnitedHealth. It also stiffened its regulations on the use of proprietary algorithms and introduced plans to audit denials across Medicare Advantage plans in 2024.

- Based on STAT’s reporting, Medicare Advantage beneficiaries filed two class-action lawsuits against UnitedHealth and its NaviHealth subsidiary, the maker of the algorithm, and against Humana, another major health insurance company that was also using the algorithm.

- Amid scrutiny, UnitedHealth renamed NaviHealth.

The companies never allowed an on-the-record interview with their executives, but they acknowledged that STAT’s reporting was true, according to the news organization.

Ross and Herman spoke with The Journalist’s Resource about their project and shared the following eight tips.

1. Search public comments on proposed federal rules to find sources.

Herman and Ross knew that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services had put out a request for public comments, asking stakeholders within the Medicare Advantage industry how the system could improve.

There are two main ways to get Medicare coverage: original Medicare, which is a fee-for-service health plan, and Medicare Advantage, which is a type of Medicare health plan offered by private insurance companies that contract with Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans have increasingly become popular in recent years.

Under the Social Security Act, the public has the opportunity to submit comments on Medicare’s proposed national coverage determinations. CMS uses public comments to inform its proposed and final decisions. It responds in detail to all public comments when issuing a final decision.

The reporters began combing through hundreds of public comments attached to a proposed Medicare Advantage rule that was undergoing federal review. NaviHealth, the UnitedHealth subsidiary and the maker of the algorithm, came up in many of the comments, which include the submitters’ information.

“These are screaming all-caps comments to federal regulators about YOU NEED TO SOMETHING ABOUT THIS BECAUSE IT’S DISGUSTING,” Ross says.

“The federal government is proposing rules and regulations all the time,” adds Herman, STAT’s business of health care reporter. “If someone’s going to take the time and effort to comment on them, they must have at least some knowledge of what’s going on. It’s just a great tool for any journalist to use to figure out more and who to contact.”

The reporters also found several attorneys who had complained in the comments. They began reaching out to them, eventually gaining access to confidential documents and intermediaries who put them in touch with patients to show the human impact of the algorithm.

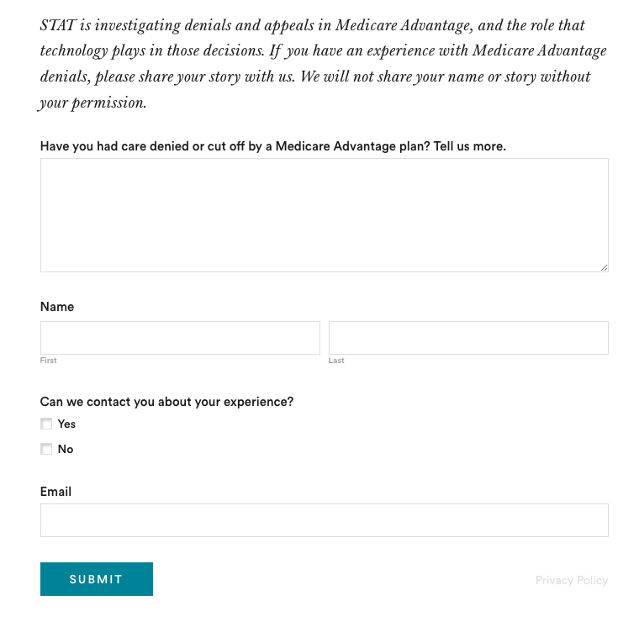

2. Harness the power of the reader submission box.

At the suggestion of an editor, the reporters added a reader submission box at the bottom of their first story, asking them to share their own experiences with Medicare Advantage denials.

The floodgates opened. Hundreds of submissions arrived.

By the end of their first story, Herman and Ross had confidential records and some patients, but they had no internal sources in the companies they were investigating, including Navihealth. The submission box led them to their first internal source.

The journalists also combed through LinkedIn and reached out to former and current employees, but the response rate was much lower than what they received via the submission box.

The submission box “is just right there,” Herman says. “People who would want to reach out to us can do it right then and there after they read the story and it’s fresh in their minds.”

3. Mine podcasts relevant to your story.

The reporters weren’t sure if they could get interviews with some of the key figures in the story, including Tom Scully, the former head of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services who drew up the initial plans for NaviHealth years before UnitedHealth acquired it.

But Herman and another colleague had written previously about Scully’s private equity firm and they had found a podcast where he talked about his work. So Herman went back to the podcast — where he discovered Scully had also discussed NaviHealth.

The reporters also used the podcast to get Scully on the phone for an interview.

“So we knew we had a good jumping off point there to be like, ‘OK, you’ve talked about NaviHealth on a podcast, let’s talk about this,’” Herman says. “I think that helped make him more willing to speak with us.”

4. When covering AI initiatives, proceed with caution.

“A source of mine once said to me, ‘AI is not magic,’” Ross says. “People need to just ask questions about it because AI has this aura about it that it’s objective, that it’s accurate, that it’s unquestionable, that it never fails. And that is not true.”

AI is not a neutral, objective machine, Ross says. “It’s based on data that’s fed into it and people need to ask questions about that data.”

He suggests several questions to ask about the data behind AI tools:

- Where does the data come from?

- Who does it represent?

- How is this tool being applied?

- Do the people to whom the tool is being applied match the data on which it was trained? “If racial groups or genders or age of economic situations are not adequately represented in the training set, then there can be an awful lot of bias in the output of the tool and how it’s applied,” Ross says.

- How is the tool applied within the institution? Are people being forced to forsake their judgment and their own ability to do their jobs to follow the algorithm?

5. Localize the story.

More than half of all Medicare beneficiaries have Medicare Advantage and there’s a high likelihood that there are multiple Medicare Advantage plans in every county across the nation.

“So it’s worth looking to see how Medicare Advantage plans are growing in your area,” Herman says.

Finding out about AI use will most likely rely on shoe-leather reporting of speaking with providers, nursing homes and rehab facilities, attorneys and patients in your community, he says. Another source is home health agencies, which may be caring for patients who were kicked out of nursing homes and rehab facilities too soon because of a decision by an algorithm.

The anecdote that opens their first story involves a small regional health insurer in Wisconsin, which was using NaviHealth and a contractor to manage post-acute care services, Ross says.

“It’s happening to people in small communities who have no idea that this insurer they’ve signed up with is using this tool made by this other company that operates nationally,” Ross says.

There are also plenty of other companies like NaviHealth that are being used by Medicare Advantage plans, Herman says. “So it’s understanding which Medicare Advantage plans are being sold in your area and then which post-acute management companies they’re using,” he adds.

Some regional insurers have online documents that show which contractors they use to evaluate post-acute care services.

6. Get familiar with Medicare’s appeals databases

Medicare beneficiaries can contest Medicare Advantage denials through a five-stage process, which can last months to years. The appeals can be filed via the Office of Medicare Hearings and Appeals.

“Between 2020 and 2022, the number of appeals filed to contest Medicare Advantage denials shot up 58%, with nearly 150,000 requests to review a denial filed in 2022, according to a federal database,” Ross and Herman write in their first story. “Federal records show most denials for skilled nursing care are eventually overturned, either by the plan itself or an independent body that adjudicates Medicare appeals.”

There are several sources to find appeals data. Be mindful that the cases themselves are not public to protect patient privacy, but you can find the number of appeals filed and the rationale for decisions.

CMS has two quality improvement organizations, or QIOs, Livanta and Kepro, which are required to file free, publicly-available annual reports, about the cases they handle, Ross says.

Another company, Maximus, a Quality Improvement Contractor, also files reports on prior authorization cases it adjudicates for Medicare. The free annual reports include data on raw numbers of cases and basic information about the percentage denials either overturned or upheld on appeal, Ross explains.

CMS also maintains its own database on appeals for Medicare Part C (Medicare Advantage plans) and Part D, which covers prescription drugs, although the data is not complete, Ross explains.

7. Give your editor regular updates.

“Sprinkle the breadcrumbs in front of your editors,” Ross says.

“If you wrap your editors in the process, you’re more likely to be able to get to the end of [the story] before they say, ‘That’s it! Give me your copy,’” Ross says.

8. Get that first story out.

“You don’t have to know everything before you write that first story,” Ross says. “Because with that first story, if it has credibility and it resonates with people, sources will come forward and sources will continue to come forward.”

Read the stories

Denied by AI: How Medicare Advantage plans use algorithms to cut off care for seniors in need

UnitedHealth pushed employees to follow an algorithm to cut off Medicare patients’ rehab care

UnitedHealth used secret rules to restrict rehab care for seriously ill Medicare Advantage patients

This article first appeared on The Journalist’s Resource and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Comments 1