We all know healthcare’s a game. But few know the rules. We think the game’s defined over a clinical encounter, starting and then finishing, when it’s actually never-ending.

It’s an infinite game. It continues in perpetuity, with the rules changing after every decision. In game theory, we call it a changing payoff, which means the likelihood of a subsequent decision taking place changes after a round of decisions have been made. Sometimes we can see starkly different outcomes after just a few rounds, even for similar clinical circumstances.

Take a female patient going in for her mammogram screening. After the first screening, she gets an email saying the results were inconclusive, so she needs to get another test. Her initial instinct is to panic, to assume the worst case scenario and rush for a repeat test. Once the second study comes back normal, her fears assuage. After a few years of this, whenever she presents with inconclusive results on her mammogram, she chalks it up to her body type and leaves things at that.

Her response to the initially inconclusive test result changed after the second study because she saw the second study came back normal. Going forward, her response to similarly inconclusive studies changed because she knew what to expect the next time around. Her payoffs changed after every test result, so her decisions changed as well. In healthcare, every decision is a game, defined by payoffs that influence the outcome. And every round is a response to a previous decision, with the payoffs adjusting in reaction.

Since the payoffs determine the rules of the game, and consequently, the likely outcome, each clinical decision made before modifies subsequent decisions that will be made. If the rules are harsh and warrant a stiff penalty, then the difference in payoffs will be more skewed and the results of the game will reflect a more extreme, one-sided outcome. But if the rules are more balanced, then the payoffs will reflect a more even outcome.

Games are funny like that. It’s less about the player and more about the rules. In healthcare, it’s less about the individual decision-maker and more about the rules that affect the decisions. Sometimes the rules are so extreme that the outcome is a direct response to a rule itself.

The best of example of this would be the legal influence in healthcare. When the legal penalty for a clinical decision is severe, the rules reflect a more extreme difference in payoffs between that decision and its opposite.

Suppose an elderly patient appears in the emergency department with altered mental status. Regardless of what may be the underlying cause of the symptoms, the patient will receive a stroke workup. Providers will order blood tests, a carotid Doppler, and a head CT, regardless of whether it’s necessary. Maybe the patient’s dehydrated, maybe there’s an electrolyte imbalance; it doesn’t matter. The downside payoff for not ordering those tests is too risky because of the legal liability that comes with failing to perform a stroke workup. So clinical judgment be damned, those tests will get ordered.

But something gets lost in all of this. If the purpose of healthcare is to optimize patient outcomes, then the rules should reflect this, and only this. The payoff of any clinical decision made by a provider should balance the likelihood of diagnosing or treating a disease based on the presenting symptoms or available information. Instead, we see rules that lead to sub-optimal clinical outcomes because the payoffs have little medical basis. The rules are defined by avoiding legal liability instead of optimizing clinical decision-making. In certain instances, the payoffs are so extreme that they effectively determine the most legally safe outcome instead of guiding toward the best-case clinical scenario.

There are consequences to this. In any game where the results can be predicted by the rules, the rules overtake the outcome in importance. In healthcare, this is what happens when the risk of legal liability overtakes the clinical benefits of a decision.

Sure, state and federal regulatory bodies are quick to say they don’t influence the practice of medicine. But if they set the rules with payoffs that are extreme to the point of predetermining outcomes, then they are defining the practice of medicine.

We like to ignore this in healthcare. And we have yet to fully appreciate how extreme payoffs affect healthcare by swaying clinical decisions. It’s time we study how patient outcomes are affected by the decisions made. We can start by applying basic decision frameworks from behavioral economics.

When we construct decision matrices to compare the payoffs of different clinical decisions side by side, we see how influential the rules are to any outcome in medicine, particularly the rules defined by legal liabilities.

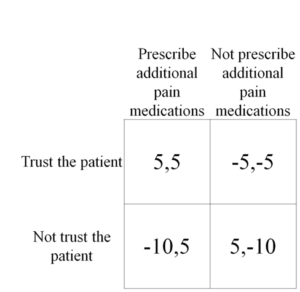

Take the following vignette: A 57 year old female patient with rheumatoid arthritis presents to her primary care office complaining of worsening pain. She’s already on opioids for pain, as well as a low dose disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD). And now, she’s asking for a bump in her pain medications. The primary care physician is presented with a series of decisions: to trust or not to trust the patient when she says she’s in pain, and to temporarily increase or not to increase the pain medications.

When displayed in a two-by-two matrix, we see the decisions side by side. On the left is the decision to trust and on the top is the decision to increase the medication. The payoff to the physician is the first number and the payoff to the patient is the second number, with the two being separated by a comma. It may appear odd that we separated the decision to trust with the decision to adjust the opioid dose, but that’s the point.

Clinical decisions made with a degree of skepticism have different payoffs because the results from those decisions are different. When you trust someone, you act implicitly, without too much guarding – like letting your friend borrow your car. But absent trust, the barriers come up. Now that same situation, letting someone borrow your car, but somebody you distrust, is met with a litany of paperwork detailing who assumes liability and how the car will be driven. In your mind, the lack of trust poses a risk, so the perceived risk of letting that person borrow your car becomes greater. So the payoffs grow farther apart.

In this clinical scenario, the payoffs reflect how trust alters a clinical decision. When a physician trusts a patient, his downside risk is perceived to be lower so the outcome is more balance, often tilting toward what’s best for the patient.

But trust does something else beyond altering the likely outcome. It not only changes the payoffs, it changes the game fundamentally by changing how the players view it. Each patient encounter is no longer seen as a single game, repeated and reenacted over and over again at each visit. It’s seen as an infinite game, ongoing and changing per clinical visit.

In such a game, the physician is more likely to provide additional pain medications because he is more trusting of her. Not just that she truly has worsening pain, but that she will use the medications appropriately and agree to decrease the medications back to its original dose later on. Both the physician and the patient make decisions in the moment based on trust, knowing that the engendered trust in the current decision will positively affect payoffs in subsequent decisions.

In contrast, absent any meaningful trust, the clinical encounter breaks down into a single decision with the full weight of legal liability squarely felt in the payoffs. There is no subsequent round because neither the physician nor the patient can see much beyond this current decision. The physician is distrustful, afraid of the legal consequences that may come from increasing her pain medication. So he makes a decision based on a payoff that is defined less by the patient’s clinical need and more on the potential legal liability. As a result, the patient suffers.

Trust turns the clinical encounter from a game with fixed payoffs restarted at each encounter into an ongoing game with changing payoffs modifying over time. It aligns the payoffs of any clinical decision with what’s best for the patient and increases the likelihood of an optimal clinical outcome.