The government just does not get healthcare. No branch understands it: judicial, legislative, or executive. They all take some drawn-up legal right, find some favorable judicial ruling, and use the pretense of law to posture a preexisting stance they find to their liking.

First, the Supreme Court used common law to eliminate abortion as a right to privacy. Now the Department of Justice seeks to protect abortion as a right to access medical care.

“Federal law is clear: patients have the right to stabilizing hospital emergency room care no matter where they live,” said Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra. “Women should not have to be near death to get care. The Department of Health and Human Services will continue its work with the Department of Justice to enforce federal law protecting access to health care, including abortions.”

While the Department of Justice and the Department of Health and Human Services are clear in their mission to provide access to abortion, what remains unclear is the exact federal law Mr. Becerra is referring to. We implicitly assume the right to access medicine exists in the Constitution, which means it is not etched in stone like other fundamental liberties – at least not at the federal level.

At the state level, it varies depending on each state’s constitution and the legislative authorities given to each state’s assemblies. In Kansas, which recently made headlines for voting to uphold abortion rights in the notoriously conservative state, abortions are considered a fundamental right in the state’s bill of rights, as upheld by the state’s supreme court in 2019.

The recently proposed amendment, which did not garner the necessary votes to pass, would have added verbiage to the state’s bill of rights that explicitly excludes abortion as a fundamental right in the state’s constitution.

Reporters heralded it as a victory for abortion rights and for democratic principles in America. With its slight leftward tilt, the media loves to portray such legislative results in Kansas and the efforts by the DOJ as valiant efforts in upholding a right most of the country agrees with.

But that perspective misses the mark and skirts over the real issue. When we remove the veneer of political bias, we find these latest initiatives to be as convenient as the common law justification used by the Supreme Court to eliminate the right to privacy. When we recontextualize medical care and clinical procedures as rights, we transform something medical into something legal.

Usually, this means we take something complex and we simplify it. Previously, we assumed abortions to be a right to privacy. That turned the medical procedure, with all its socioeconomic drivers, into a figurative mile-marker, measuring the legality of abortions into a rubric of weeks.

Now, instead of redefining the concept of rights as it pertains to complex medical issues in a post-Roe world, we look for other existing rights into which we can tuck abortion. Currently, it is the right to access medical care. Until we find a legal argument to overturn that right. And then we will find another right. On it will go, a proverbial game of legal wack-a-mole in which medical procedures find convenient legal logic to justify it – and overrule it.

When we put forth simplified laws that reduce the complexity of abortion into pre-defined rights, the legal logic both in favor of and against the issue loses any relevant context.

Each argument is nothing more than an exercise in rhetoric. The clinical fundamentals underlying the medical purpose of abortions are lost in the political maze of legal rights and judicial precedence.

Instead, we need to properly orient our understanding of healthcare and law. We have a discipline that focuses on doing just that – medical jurisprudence. Right now we relegate it to DNA samples and overturning false convictions based on fabricated scientific evidence.

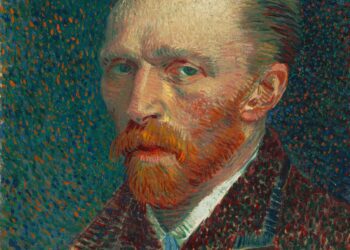

But there was a time when the brightest minds in medicine contributed to medical jurisprudence. Luminaries like Dr. William Osler or Dr. Stanford Emerson Chaille, who contributed to the field and provided texts that remain applicable today. They wrote essays detailing the moral duty of physicians and the role they play in society, adjudicating over both the individual patient and broader public health.

But in recent years, we gravitated toward the quantitative, until all that mattered was what could be measured. We lost sense of the qualitative aspects of medicine. The philosophy of medicine was replaced by the business of healthcare. The legal world entered and introduced concepts like rights to define medicine. Whereas before we had physicians pontificating on the ethics of medicine and the boundaries where ethical considerations become legal liabilities, we now have lawyers reducing all of medicine into some form of rights.

It is time for the medical community take back medicine, so we can once again define medicine, not in terms of legal rights, but through its philosophy.