Funny how the things we hold true often rely on the flimsiest of pretenses.

In recent weeks, two diseases we have long assumed to be well-defined – dementia and depression – were suddenly much less of both.

The most prominent study analyzing the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease, the most well-known form of dementia, which shaped how we diagnose and treat it, was found to be based on doctored imaging studies.

The most widely accepted theory of depression, the chemical imbalance theory, which ushered in a wave of serotonin laden antidepressants, was finally put out of its misery and laid to rest.

The media reported what most physicians and scientists have known for some time: that the two conditions are both pathological and behavioral disorders with extensive socioeconomic correlates extending beyond the traditional confines of clinical medicine.

We now see words like complex in media outlets far more often than we once did when describing clinical diseases. It is a far cry from the convenient cause and effect narratives that have dominated news stories over recent decades. And we should laud it. It is a much needed change.

But it is emblematic of a more fundamental shift in medicine, away from tangible data and toward a blend of what we see and what may not be apparent. Away from evidence based medicine, the system of thinking through clinical problems with evidence and logic.

It first emerged in the late nineteenth century and was met with skepticism among clinicians of the day. But over time, as we incorporated more technology and capitalism into medicine, we grew to accept it until it came to dominate all of healthcare.

In our rush to quantify everything medical, we hastily constructed convenient cause and effect relationships. For a given symptom, we assigned a specific disease. We became reductionists even after we were warned against such thinking by the previous generation of philosophers and physicians.

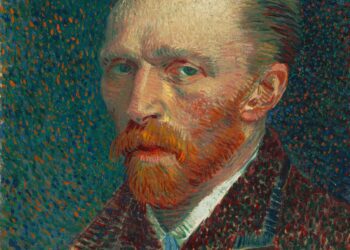

Ralph Waldo Emerson and Dr. William Osler were among the loudest voices decrying the trend toward materialism in medicine. A patient’s disease is not the cumulative sum of his or her symptoms, they cautioned. We heard it, but we did not listen. We were too enamored with data and dollars to see through the fallacies of evidence based medicine.

We ignored bias in favor of the obvious. We overlooked subtle inconsistencies in data to make way for career-enhancing groundbreaking studies. In the end, we got what we deserved: poorly constructed clinical theories based on overly simplified narratives that reduce medicine into convenient cause and effect.

Now we are beginning to see the error of our ways. When we rely too heavily on evidence and logic to draw clinical conclusions, we reinforce faulty clinical practices and are left with poor patient outcomes.

The absence of evidence does not make a proposed clinical diagnosis false. Just like the presence of evidence does not prove it true. Appearances are notoriously deceiving in medicine. It is why the physicians of lore valued direct experience more than anything else. The direct perception has always been more valuable than any logical conclusion or data.

We call it medical empiricism, the study of patients based on direct sensory experience. Philosophers call it a dialectic, the exchange of ideas and words that converge into a clinical diagnosis.

It is time to once again employ this approach to patient care in medicine, not just in theory, but in the practical application of day to day medicine. This would require us to unwind a lot of established norms in medicine, including institutional practices that we consider sacrosanct. But it is the only way we can advance.

Otherwise we will be mired in half-baked theories that unravel over time, only to be rewrapped in another veneer of cause and effect. It is what inevitably happens when we let evidence based medicine dictate patient care.

Comments 1