Abortion is the most controversial medical issue in the United States, precisely because it is not seen as a medical issue. For many, it is an ethical or even a religious issue.

These varying perceptions lead to different stances on abortion, some in favor and some against. But no matter the position taken, it is assumed with a particular vigor unique among all medical issues. We scrutinize every aspect of the procedure – whether it is the process of obtaining informed consent or the number of weeks of pregnancy in which it is legally permissible.

What we have not considered is the impact of technology on the abortion experience. We see abortion as a process, one that beings with a presumed ill-conceived pregnancy that ends with a procedure to end it. We chronicle and litigate every step along the way, but we never consider how those steps may change through different technological interfaces – namely telemedicine, which has altered the calculus for many seeking abortions.

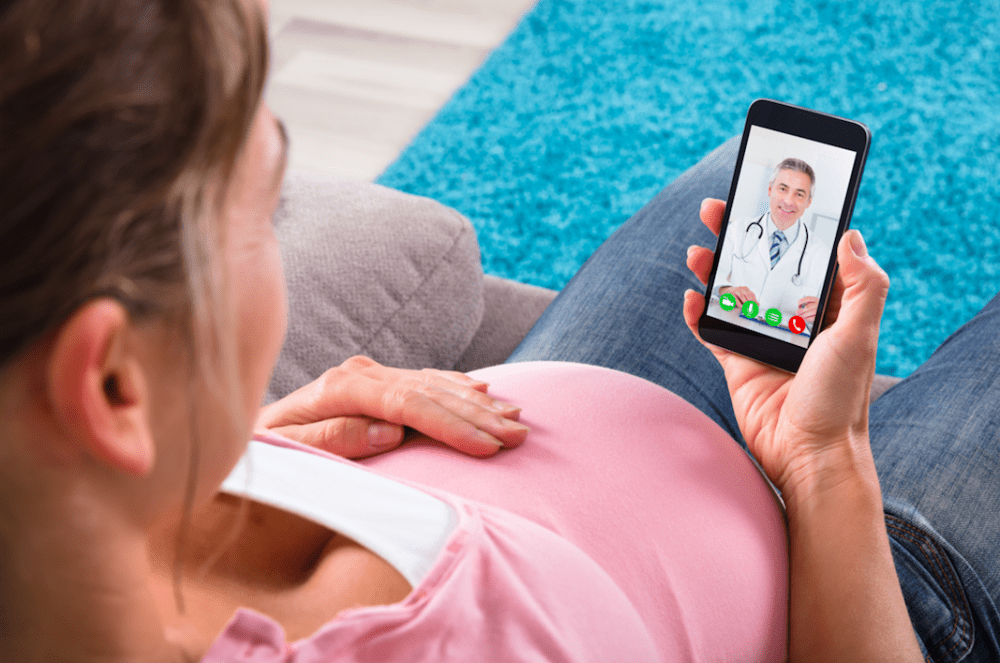

Now patients can obtain abortion medications without having to visit a physician in person. In late 2021, the FDA modified its restrictions on Mifepristone, a medication used to induce an abortion. The new regulations effectively enable abortion via telemedicine in more than half of the country. Patients can see a physician at their own convenience and have abortion medications mailed to their homes.

This shift in regularly policy changes the process of obtaining an abortion. Women no longer experience the existential shame of seeking abortion medications at a medical facility. It is far more convenient, far timelier. As a result, medication-based abortions are the most requested way to obtain the procedure. The increase in availability has increased the number of requested abortions. For an issue where every aspect of the experience is regulated, this has ignited an equal but opposite increase in policy restrictions.

In Tennessee, a state where more than 75 percent of abortions occur within the first 10 weeks of pregnancy, where the state’s chapter of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has endorsed abortions as a safe procedure, obtaining abortion medications via telemedicine has been outlawed. State regulators are also seeking to outlaw mail-ordered abortion medications, which if passed, would require those seeking an abortion to see an abortion providing physician in-person for every aspect of the procedure.

The issue at hand, ostensibly, is one of access. But in reality, it is one of perception. We think that when we limit access to abortions, we are addressing a perceived good. But we are merely restricting individual choice. Patients, no matter what, will always seek abortions. When the option of obtaining abortion medications becomes increasingly available, more patients seek it.

From a medical standpoint, there is no logic. But when we view abortion outside of its medical context, the perception of the procedure falls prey to moralizations that are anything but clinical in nature. And it is through this lens that those who seek restrictions find their logical basis.

But if access to healthcare is a fundamental right afforded to all Americans, one included within the framework of the first amendment no less, then what is the basis for such restrictions?

The question strikes at the heart of healthcare liberty, and will grow more pronounced as we continue to accept more and more technological interfaces in patient care. Law reflects the will of society, and as the perceptions of society change, so do its laws. Abortion, at some point in the near future, will be less about the procedure itself, and more about the right of access.

This will prompt questions regarding the definition of access in healthcare, and whether restricting technological access to healthcare services that we may not agree with is constitutional.