Stephen Soumerai, Harvard University and Ross Koppel, University at Buffalo

Depression in young people is vastly undertreated. About two-thirds of depressed youth don’t receive any mental health care at all. Of those who do, a significant proportion rely on antidepressant medications.

Since 2003, however, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has warned that young people might experience suicidal thinking and behavior during the first months of treatment with antidepressants.

The FDA issued this warning to urge clinicians to monitor suicidal thoughts at the start of treatment. These warnings appear everywhere: on TV and the internet, in print ads and news stories. The most strongly worded warnings appear in black boxes on medication containers themselves.

We are professors and researchers at Harvard Medical School, the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine and University at Buffalo. For over 30 years, we have been studying the intended and unintended effects of health policies on patient safety.

We have found that FDA drug warnings can sometimes prevent life-threatening adverse effects, but that unintended consequences of these warnings are also common. In 2013, working for the FDA itself, we published a systematic review of the effects of previous FDA warnings on a variety of medications. We found that about a third backfired, resulting in underuse of needed care and other adverse effects.

In our more recent study from 2020, we found that the FDA antidepressant warnings have led to reduced mental health care and increased suicides among youth – even though researchers have yet to find a clear link between antidepressants and increased suicidality in young people.

Further, despite the warnings, monitoring by clinicians of suicidal thoughts at the start of treatment has not increased from its tiny rate of less than 5%.

Youth suicides rose following FDA warnings

For our 2020 study, we obtained 28 years of data, between 1990 and 2017, on actual suicide deaths in the U.S. among adolescents and young adults. We used data from the WONDER Database, maintained by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which contains mortality counts based on death certificates for U.S. residents and population counts for all U.S. counties.

We found that during the pre-warning period, there was a 13-year stable downward trend in youth suicides, following availability of new and safer antidepressants.

That trend reversed, we found, soon after the FDA began antidepressant warnings in late 2003. Youth suicide deaths increased significantly.

Then we applied our findings to the whole U.S. population of adolescents and young adults. The results of that analysis suggest that there were almost 6,000 additional suicide deaths in just the first six years after the FDA issued the boxed warnings, from 2005 through 2010. The rates also continued to rise thereafter.

Over this same time period, older adults – whose depression is not targeted by the warnings – experienced much lower increases in suicide.

Fewer depressed youths got treatment

Our findings align with a growing body of research that confirms these warnings have had serious unintended effects: scaring many patients, as well as their parents and doctors, away from both antidepressant medications and psychotherapy that can reduce major symptoms of depression.

These studies include a rigorous 2017 study that analyzed mental health care trends among 11 million youths who rely on Medicaid for insurance coverage. This research documented that immediately after the FDA warnings began in 2003, there was a sudden and sustained 30%-40% drop in youth visits to doctors for all depression care, including antidepressant prescriptions.

Seven years after the first FDA warning, doctor visits for depression by young people had dropped by around 50%, compared with the pre-warning trend, thus severely reducing treatment and suicide prevention.

That trend included Black and Latino youths, who have already long suffered from undertreatment.

Almost simultaneously, youth poisonings via prescription drugs, such as sleeping pills, went up. Research has shown that prescribed medications are a widespread method by which young people attempt suicide. This finding adds to the evidence that the antidepressant warnings increased suicidal behavior.

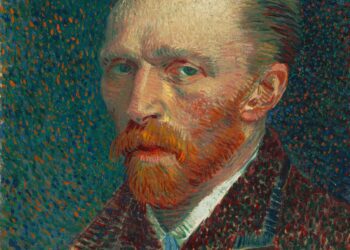

Katarzyna Bialasiewicz/iStock via Getty Images

In 2018, researchers reported on two patients in their 20s whose experiences illustrate the potential real-life impacts of the black-box warnings. Both young adults had been prescribed antidepressants for major depression and severe panic attacks, but they refused to take them because of the FDA’s message.

Their conditions worsened, and eventually both attempted suicide. Fortunately, family members were able to intervene in time, and each young adult was then hospitalized.

After they accepted the reassurances of hospital psychiatrists that the benefits of the medications would likely exceed any risks, both patients began to take their prescribed antidepressants. These medications, combined with talk therapy, alleviated their symptoms without intensifying suicidal thoughts.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

Reevaluating the warnings

As scientists, we are trained to always seek potential alternative explanations – some additional factor not included in the research – that could explain the reduction in care or increase in suicides that we and others have recorded in our studies.

However, the sudden, simultaneous and large effects – all of which directly reduced treatment and increased suicidal behavior – strongly suggest this is not a coincidence. It is unlikely that any outside factor can account for the multiple parallel effects on depression care, suicidal behavior and suicide deaths.

A large and growing body of evidence shows that the FDA’s black-box warnings on antidepressants need to be reevaluated.

More generally, there’s a need for independent researchers to monitor the effects of FDA warnings on public health – both intended and unintended.

Stephen Soumerai, Professor of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Harvard University and Ross Koppel, Professor of Medical Informatics and Adjunct Professor of Sociology, University of Pennsylvania; Professor of Biomedical Informatics, University at Buffalo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.