Slouching in his chair, with his legs sprawling over a coffee table and his arms dangling to each side, he drops his head. It hangs lifelessly above his heaving chest.

His name is George Sanders. His friends call him George. But these days, he mostly goes by Mr. Sanders or Mr. S, depending on the nurse caring for him at the time. His now gaunt frame belies a once husky exterior hardened over years of football in his youth and construction labor throughout his adult life.

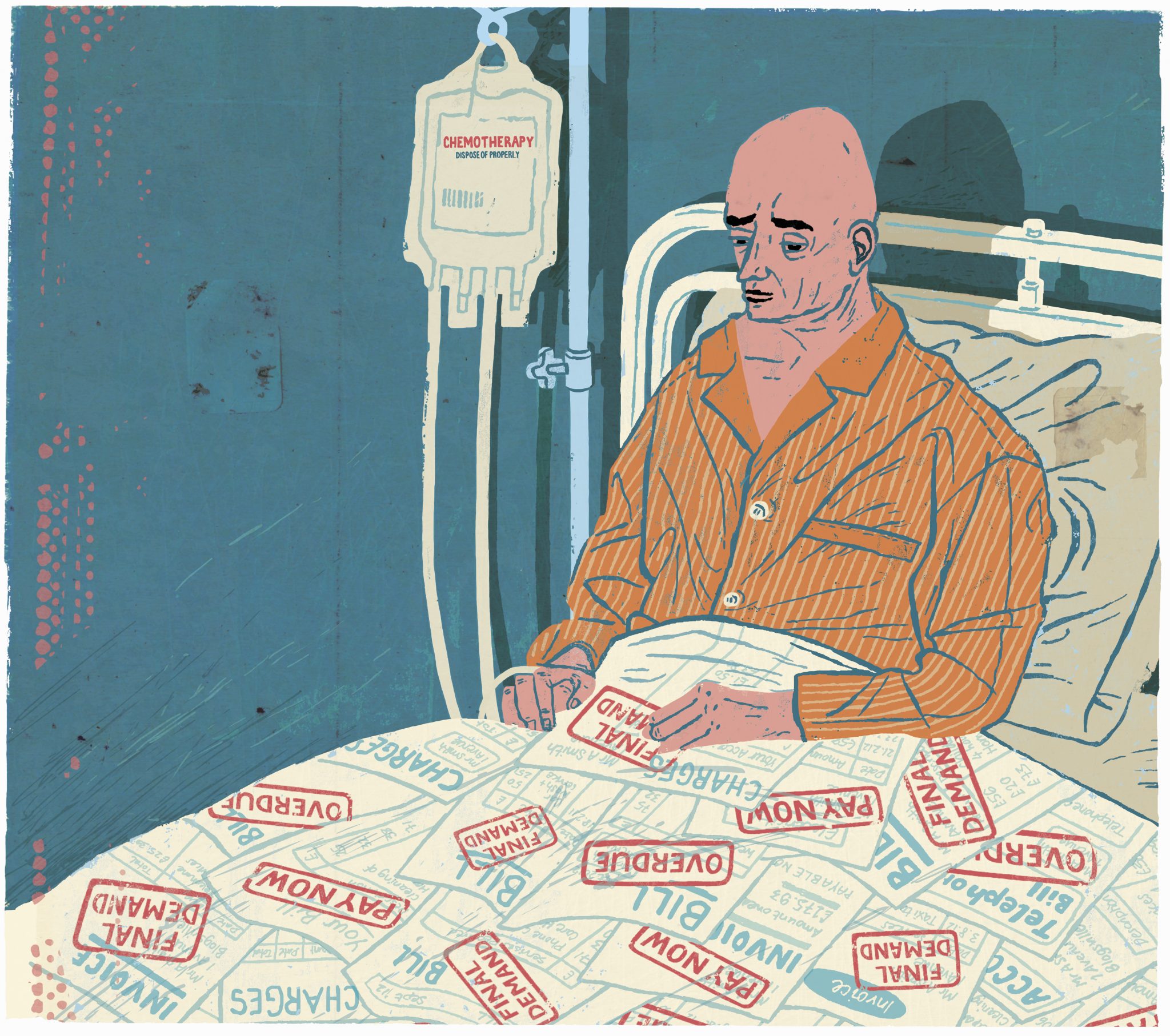

On the table situated between his legs, is a disorganized pile of papers, each sheet creased a particular way and oriented at different angle. Mr. S, known for his sarcastic sense of humor, jokes that the pile of papers could pass for some abstract art. But there is no humor on Mr. S’s face right now. There are only strokes of guilt, shame, and regret.

The pile of papers is a collection of bills, with each company, creditor, and collection agency taking the liberty of folding their bill in a particular manner, each contributing to the art. That together produces a financial impact showing clearly upon Mr. S’s face.

He is a cancer survivor. He has the t-shirt to prove it. But in his battle with cancer, a battle for his life, he lost everything around him.

He was first diagnosed three years ago in the Spring. He remembers staring at the budding leaves on the trees guarding the front lawn when he first got the news.

“The tree symbolizes my fight. The tree always persists, no matter the time of year, the score of the football game, or the location of the construction site. Persist and fight through – that all I know”, he said, vowing then to fight the cancer with everything he had, clenching his fist with the same vigor used to tackle an opponent on the football field.

A few weeks and a biopsy later, he was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. He rushed to learn everything there is to know about his new disease, his new battle. He joined patient advocacy groups, studied treatment protocols online, and emailed his physician every question under the sun on treatment options.

He broke the news to his two sons. He informed them of the upcoming battle. He was all in and he wanted his family to know.

He created a binder to compile his notes and research, separating it into multiple folders, each with a designated label – starting with ‘medical notes’ and ending with ‘family discussions’. He organized everything related to his cancer. Every future clinic visit and every potential follow up that would transpire in his life, whether directly or tangentially related to his cancer diagnosis, had an open spot in a folder. He was ready.

During the first physician visit after learning of his cancer diagnosis, he came armed with this binder, now brimming with information. When he was told, based on the spread and biopsy results that he would need chemotherapy, he didn’t blink twice. He was already mentally prepared.

He showed uncanny resolve, having already developed an emotional shield that would filter any anxiety and concern no matter how bad the news. He fought the uncertainty of the unknown through the diligence of planning.

He discussed the latest cancer research with his physician, discussed the effects of the chemotherapy, and learned nuanced details about the cycles and drugs that would define his life for the next two years.

After leaving the physician’s office, he called his insurance carrier to learn about his coverage options. He had a Medicare based insurance plan, but the plan itself was administered by a private insurance company.

He soon learned his medical coverage was not a fixed number covering the cost of care. Rather, it was an ongoing negotiation against a bureaucratic behemoth, wielding an arsenal of prior authorizations, claims denials, and reinsurance packages against Mr. S.

He attacked the behemoth with phone calls, emails, and well-timed letters, maximizing the coverage of his chemotherapy. He sent medical records and imaging reports upon demand, and spoke to anyone who would listen, be it care managers or medical directors or anyone else conjured up by the behemoth.

He resent whatever he needed to resend, and called whomever needed to be spoken with. He picked up certain tricks along the way, like recognizing sometimes faxing something twice on different days increased the likelihood that they would be received.

Eventually Mr. S learned that he was fighting a battle on two fronts – the cancer itself and the cost of treating the cancer. Both fronts took their toll. But he was up to task.

He grew adept at balancing the side effects of the chemotherapy with the never-ending financial hurdles. Sometimes he sent a barrage of emails in the middle of receiving chemotherapy, shuffling medical records digitally between the hospital and his insurance carrier while ensuring his IV line remained fixed in place. For Mr. S, no task was too cumbersome, no coordination too difficult.

His rest days became insurance phone call days. His side effects included the burning, the fatigue, and the vomiting – as well as the lingering angst of not knowing how he would finance it all.

His insurance carrier paid a significant amount of the upfront costs, but like his vomiting, the costs kept coming. Nevertheless, he persisted, meticulously organizing every bill that came in the mail.

His efforts were quickly rewarded. He received 110% of the allocated coverage for patients diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma.

When Mr. S found out he would be fully covered, he felt a reinvigorated sense of relief. Like any battle, victory uplifts morale. And through the relief, the side effects from the chemotherapy diminished, and he felt a decisive victory would be just around the corner.

That corner proved farther than Mr. S had first anticipated. Two years after he was diagnosed he developed an infection, which initially began as a simple cough. He was then told it was pneumonia, but the treatment was more than what Mr. S had understood the treatment for pneumonia to be.

What Mr. S contracted was not regular, community acquired pneumonia. It was a more severe pneumonia that only presents in patients with compromised immune systems. As a result, Mr. S had to go to the hospital and receive antibiotics intravenously.

For Mr. S, pneumonia was pneumonia. He didn’t understand why he needed to stay at the hospital. But in typical fashion, he steadied his resolve and approached this infection as he had approached the cancer, exhibiting the same diligence – obtain the medical records, call the insurance company, research the treatment options, and study the side effects – nothing he couldn’t handle.

But this time something was different, he heard a lot of ‘let’s wait and see’, whereas before he had received a definitive response.

“Let’s wait and see what the pneumonia culture shows.”

“Let’s wait and see how the insurance policy covers this pneumonia.”

His physicians, however, didn’t wait and see. They admitted and treated. And after five days in the hospital, two of which were spent in the ICU, he was discharged – not to his home, but to an assisted living facility.

Part of the problem with this ‘wait and see’ policy was that neither the physician nor the insurance company could easily determine the cause of the pneumonia. And its cause would determine its coverage.

At first Mr. S didn’t understand how they could treat something without knowing the species of bacteria. But the antibiotics covered a range of bacteria, so regardless of the exact species, the antibiotics administered were strong and wide-ranging enough to cover the pneumonia.

However, the antibiotics couldn’t cover the cost of treating the pneumonia, which varied based on the type of bacteria.

If the pneumonia was due to a bacteria commonly seen among patients receiving chemotherapy, then he would receive full coverage. If the pneumonia was from some other bacteria not usually seen among patients receiving chemotherapy, then he would receive only partial coverage.

It was all unsettling to Mr. S. In the beginning everything was organized. Now everything seemed ad hoc and contingent. The uncertainty made Mr. S anxious – and there was no amount of planning that could resolve it.

“Why does the source of the pneumonia matter? I was treated and now I’m fine!”

For most of us, his anxiety seemed like a rational response to the changing events. But time doesn’t rationalize, it simply marches forward.

Within a few days, Mr. S received the first of many bills. It was a hospital bill, thirty-five thousand dollars for five days.

He reflexively called his insurance carrier, only to receive another evasive response. They were still awaiting the pneumonia culture – “unfortunately we need to wait and see”. He then called the hospital, navigated through a jungle of phone transfers to the pathology department and spoke with the on-call pathologist. Only to learn the preliminary results were inconclusive and the final results were still pending – “we will need to wait and see. I’m sorry”.

Mr. S held the phone to his face despite ending the call. He was not sure what to do, and the uncertainty began to gnaw at him. Lacking anything to prepare, he tried to assure himself with self-talk.

“If they want me to ‘wait and see’, then wait it is”, which would have worked out well enough, if not for the thirty day deadline on the bill, prompting another called the hospital, this time to the billing department.

He asked what would happen if he didn’t pay the bill on time – “straight to collections” – or if he needed just a little more time to pay – “straight to collections”.

Now Mr. S encountered a third front of the battle, time.

With the final culture report, he could coordinate the bill between his insurance carrier and hospital, and pay the amount without having to worry about collections.

But day after day, week after week, he continued to wait. He grew less hopeful as time went on.

Things that took hours now took days. It became apparent that his insurance carrier would not budge or dole out payments any time soon. They seemed to move in weeks while he needed to move in days. But the deadline on the bill remained, approaching more quickly than ever.

So he did what he had done since the beginning, when he first received his cancer diagnosis, he persisted.

He reached out to his two boys to ask for financial support. Neither son was in much position to help, as both were living paycheck to paycheck working as non-union laborers.

His ex-wife left him years ago and his manly pride would not allow him to pursue that option. He searched the internet and learned his bank offered personal loans to account holders albeit at high interest rates.

Mr. S justified that he could pay the loan once the culture report came even though three weeks had since transpired. His desperation impacted his decision-making. He forgot the pneumonia may or may not qualify for coverage, depending on the bacteria that caused it. He simply thought, “if I can make this payment, then things will work out”.

And with that, he took out a personal loan to cover half the amount owed. Seeing some level of payment come in, the hospital’s billing department suddenly became amenable to negotiating a payment plan. Together they negotiated a plan to space out the remaining payments over set installments.

Now, instead of one big problem, Mr. S had two smaller problems – the loan payments and remaining hospital payments. He terminated most of his utility bills and cancelled any unnecessary recurring expense. He spoke to his landlord and subleased an extra room in his apartment. With his age-earned fixed income and reduced expenses, he calculated he could cover the two payment streams.

“This is the price of persistence, but I’ll be damned if I let this cancer beat me.”

In a few days, he received a call from a hospital nurse that the culture report was ready – “bring it”. He knew what was at stake financially.

He scheduled an appointment for the next day. A few minutes later he called the pathology department. Again he navigated through a jungle of phone transfers before finally reaching the on-call pathologist. He asked for the results, this time with an unusual timidity in his voice.

“Well, based on the bug, it seems like you got this because of the chemo. We see patients on chemo get this bug all the time. Sorry to hear. Hope you get well”.

Mr. S found the pathologist’s response amusing. He had been well for weeks, at least medically. His ailment was strictly financial. And with one phone call, the pathologist gave Mr. S the cure.

Now knowing the cause of the pneumonia, and more importantly knowing he would be fully covered, Mr. S called his insurance carrier. Only to be met with a rude introduction.

“Sir, before we continue, I have to inform you that you are past due on your premium.”

“My what?”

“Your premium – what you pay us monthly.”

“I thought you were waiting on the culture report. You told me you need to see a report before you can provide coverage.”

“What does that have to do with your premiums?”

Mr. S froze in silence. His hands tensed over the phone, gripping it tighter and tighter. His mouth went slack. In his haste to secure a loan covering the hospital bill, he had incorrectly assumed the insurance premiums were on hold until the carrier finalized the coverage amount.

Now he realized the premiums never stopped – the fourth front of the war.

First it was the hospital bill, then the deadline on the bill, then the loan payments, and now the insurance premiums – “now what am I going to do?”

He was under water. He could barely survive with two payment streams. But with three payment streams, he would drown – and he knew it.

He beat cancer. He beat chemotherapy. He beat pneumonia from the chemotherapy. He even beat time, if for just a few days. But he could not beat his payments.

He laughed sarcastically – “it would have been better if I just died”.

Days turned to weeks, and weeks turned to months. Over time, Mr. S lost the original persistence through which he had fought so bravely. The persistence turned into indifference, and Mr. S turned into a broken man.

He threw away his binder. He let bills go unpaid. He let the mail collect on the coffee table. He stopped fighting. He created a stack of envelopes and letters, a pile of bills from the hospital and the insurance carrier. Soon the pile included notices from collection agencies.

Over time, the pile grew.

And now, it appears as an expression of art.

“How abstract” – the now gaunt Mr. S taunts the pile, sitting lifelessly in a chair in front of the coffee table as his eyes fixate on the pile before him.

He senses the pile mocking him. The longer he stares, the louder the insults become.

“All that persistence?”

“All that fight?

“For what? Look at you now.”

He continues to stare at the pile. He slides lower into his chair, now in a full slouch. He whips his feet onto the table, each leg on either side of the pile, straddling it.

“What’s the matter?”

“Can’t figure out what to do?”

“What about the tree?”

His arms fall to each side. He begins heaving as a way to calm his nerves.

The pile casts a vivid tint of emotion that overwhelms him. He is now immersed in guilt, shame, and regret. Each emotion has its own distinct tint. That together forms a brightly growing haze. He squints but the light is too much. It forces his eyes to close.

He feels the effects transforming him.

He feels shame for not anticipating the pneumonia, something he read about and feels he should have been better prepared for.

He feels guilt for not thinking about his financial risks, something he reviewed in the insurance policy but did not consider important at the time given the medical risks he was facing.

He feels shame for digging himself into financial debt, for taking out a loan he couldn’t pay, leaving him buried under a pile of growing medical debt from which he won’t recover.

Mr. S prepared for every medical risk and complication in battling the cancer and chemotherapy, but he did not anticipate the financial toxicity – “and that’s what’ll kill me.”

At this moment, he drops his head.