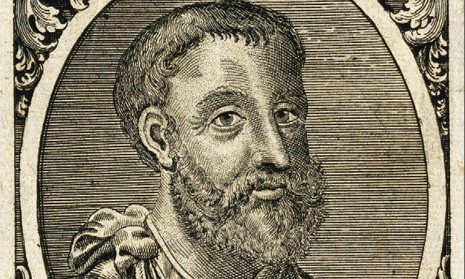

The “prince of medicine” was how Andreas Vesalius described Galen of Pergamum in the second, 1555, edition of his monumental study of human anatomy, De Humani Corporis Fabrica. By then, Vesalius knew how seriously Galen was in error because ancient Greek and Roman taboo had compelled his second-century predecessor to dissect only animals. Still, Vesalius acknowledged a deep debt.

Galen’s reputation as the leading anatomist of antiquity lives on. The most modern edition of his works, in 22 volumes, contains one-eighth of the surviving corpus of classical Greek literature.

But how many of us know about Galen’s life between AD 129 and circa 216? It was eventful and fascinating, whether in his native Pergamum, a Hellenistic city of the Roman Empire in what is now western Turkey, or in scholarly Alexandria, or in imperial Rome, as historian Susan Mattern vividly shows in The Prince of Medicine: Galen in the Roman Empire. It is “the experience of medicine in antiquity” she aims to convey to a modern reader—so utterly different from our experience, but also in some ways familiar.

Galen treated dying gladiators, for example, and thereby disproved Aristotle’s notion that the heart was the seat of reason, by remarking that a gladiator wounded in the heart remained lucid until death. He owed this particular appointment partly to his exceptional audacity in public vivisections. On one occasion, he disembowelled a live monkey and then, after challenging his dumbfounded rivals to act, replaced and secured the intestines in the hideously suffering animal.

On another occasion, he was at home, debating with his household slaves what to do with a rancid cheese, when an old man appeared at his door carried on a litter because he was arthritic with “chalkstones” (Galen’s term). Spontaneously, Galen blended in a mortar some cheese with pickled pig’s leg and applied it to the joints. This plaster apparently caused the skin to rupture and the chalkstones to ooze away through the wound, over a period of several days. The patient was probably suffering from gout. Although the cheese made no obvious contribution by modern thinking, the man procured a second rancid cheese to continue the treatment.

Having gained a stellar reputation in disease-ridden Rome and returned to Pergamum, Galen was recalled by the emperor Marcus Aurelius in order to accompany his army against “barbarian” German tribes. Galen, who apparently never bothered to learn Latin and was ambivalent about joining the Roman elite, wriggled out of what he guessed would be a protracted and gruelling war. Later, however, he learnt that the emperor had permitted dissection of one or more of the slain enemy, and regretted his evasion. “Regarding medical research his passion was intense and unambiguous”, Mattern argues. “There can be no doubt that if he had known he would be allowed to dissect a human, he would have braved the perils and discomforts of the campaign and endured the importunities of the emperor.” As for his colleagues fortunate to have dissected German corpses, Galen showed only scorn. They “did not learn more than butchers know”, he wrote.

Galen’s relationships with his medical contemporaries tended to be highly competitive, even cut-throat. With his intellect, skill, and daring—trained by 4 years as a physician to the gladiators in Pergamum—Galen usually worsted his professional rivals, while also saving his patients. Most of the competition was inevitably very public, taking place in the sickroom, surrounded by the patient’s family, friends, and other doctors. But Galen upped the ante by also offering “anatomy-as-spectacle”: demonstrations of animal vivisection while surrounded by scrolls containing the anatomical works of other physicians. He would ask his audience to name a part for dissection, then operate on the struggling creature and show how reality differed from the anatomy described in his rivals’ manuscripts.

According to Galen, he never charged a patient a fee, and regularly treated the poor for no personal advantage. The only payment he mentioned—a huge gift of 400 gold coins—came from his old friend and patron, the senator and ex-consul Flavius Boethus, for curing his wife. Mattern supports these claims, writing that: “He was a gentleman, a Greek, a leading citizen of Pergamum.

His lifestyle came to him by birthright; but his skill and reputation, by hard work, exhaustive study, experiment, experience, and proven superiority over his rivals.” However, she does criticise Galen’s “enthusiastic endorsing” of the therapeutic practice of bloodletting despite his knowing doctors who had killed their patients by taking too much blood, thereby contributing to the suffering and death of many patients in future centuries. Having read this scholarly, gripping, and often gory biography, one appreciates, exquisitely, the author’s conclusion that Galen, though “not necessarily a good man”, could still be “a good doctor”. Perhaps this has been true of many of the greatest physicians.

Source: The Lancet