There is little new knowledge in this world. Most of it is old information rehashed. Take the ever increasing encroachment of law into medicine. It is nothing new. The physicians of yesteryear predicted it well in advance.

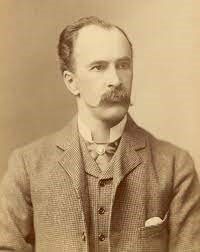

One physician in particular, Dr. William Olser of John Hopkins Health System, warned what would happen should the legal profession invade the province of medicine. His premonitions were chillingly prescient.

“It is mortifying to record that in criminal cases, the laws of some of our States continue to regard ‘quickening’ as proof of the very dawn of life.” Dr. Stanford Chaille of Tulane University, another great physician in his own right, wrote in his 1876 treatise, Origin and Progress of Medical Jurisprudence. Medicine has undoubtedly advanced since then, but the laws unfortunately have not.

Sadly, the Common law framework upholding the Constitution ensures this. Originating in Great Britain, Common law did much to advance society at that time, but it remained conspicuously absent of any provisions detailing how medical knowledge should apply the administration of justice. Its progenitor, William Blackstone, was fiercely religious, and therefore, by mid-eighteenth century logic, fiercely opposed to medicine and science. He once compared his belief in witchcraft to his faith in God.

“To deny the possibility, nay, actual existence of witchcraft and sorcery is at once to flatly contradict the revealed word of God.”

His influence on the Founding Fathers of the United States and the legal framework of the Constitution is sacrosanct. But his legacy on modern medicine is anything but immaculate. In fact, Blackstone’s own writings were used as precedent during the Salem witch trials.

This is an inevitable outcome of prioritizing legal precedent over clinical principles. The lingering antagonism to modern medicine remains the lasting legacy of Common law. And it limits how much medicine can influence law.

While medical jurisprudence derives its analysis through every specialty of clinical care, the law determines how much it will impact the administration of justice. In such a system, medicine will be forever subservient to law. This leads to inevitable conflicts that strike at the heart of each field.

Law requires closure, a verdict. For any crime, we must have an acquittal or a conviction with punishment. Law requires finality. In contrast, in medicine, we have no such finality, only progress: slowly affected change that moves forward as we glean new knowledge and apply new clinical principles into patient care. Because medicine has no closure, it looks at chance and uncertainty differently than law.

This creates immediate conflicts with law, since the two heavily determine legal outcomes. If one side has a more charismatic expert witness, then that side may win by swaying the jury by sheer force of personality. Many high stake court cases involving health issues were decided in such ways. Law focuses on individual pieces of evidence: a fact, a witness, a singular data point. In contrast, medicine focuses on the whole patient: the constellation of symptoms, the entire clinical presentation. The frames of reference are diametrically opposite.

In medicine, uncertainty is inherent in every clinical decision. We accept it as part of the standard of care. In law, uncertainty becomes a liability, to be simplified until it no longer exists – at least in our minds.

The law creates simplified narratives that win over complex clinical nuances. Since law trumps medicine, legal rhetoric reigns over medical decision-making. And as law and medicine advance technologically, medicine will inevitably gravitate toward the quantitative parts of medicine – because medicine can only grow under the influence of law.

This has done some good, no doubt. It has also led to failures, sometimes in equal parts. We developed world class vaccines in record time, but we cannot overcome vaccine hesitancy or mistrust in data.

Law has done much for the science of medicine, but little for its art. As long as law supersedes medicine, only the science, or the quantitative, will prevail. However, medicine is both an art and a science; or as Dr. Osler describes it: “Medicine is a science of uncertainty and an art of probability”.

We will always have unknowns in medicine. But law requires that we reject uncertainty to achieve closure. In light of such a contradiction, even the concept of truth differs.

“That cannot be a fact in law which is not a fact in medicine; that cannot be health in law which is a disease in fact.”

These were the words of a nineteenth century American judge serving on New Hampshire’s Supreme Court, but it might well apply to all health legal cases. The legal system places law and medicine at odds, and when conflict between the two becomes inevitable, we prioritize law over medicine.

As a result, medicine has succumbed to the tendencies of law and advanced in a way that minimizes legal conflict. So we need to legally justify most, if not all, clinical decisions for patients. We have abortion laws that worsen abortion outcomes. We pit gun rights against gun violence outcomes while shamelessly feigning incredulity when suspecting the two may be related. And we rather pray over those who succumb to fatal overdoses than consider clinical techniques of harm reduction to save their lives.

It seems all of medicine is doomed to a subservient existence under the yoke of law. But there is a solace, a lone recourse that can transcend the tyranny of law over medicine: It is to exemplify the best of clinical care, to be a great physician. This was the resounding message of Dr. Osler a century ago, and it rings true today – perhaps even more so.

Dr. Osler saw medicine as more than a profession. He saw it as the ideal embodiment of a person. He saw the balance in the art and science of medicine as an external analogy to the internal hopes and fears that define great physicians. For him, uncertainty is not something external that appears only when making a clinical diagnosis. It is inherent to how physicians think. Since such thinking leads to clinical decision-making, the internal analysis reflects the external clinical outcome.

It is a balance that we must forever keep. Indeed, clinical progress is defined through this balance. Therefore, we have no closure in medicine. We are always progressing towards the absolute truth, the most certain diagnosis, the optimal treatment. We may not achieve it, but we must continue the pursuit. Accept the unattainable, for we know it is impossible, but chase after it nonetheless. This is the premise of Dr. Osler’s famous balance.

To understand his wisdom is to see beyond the superfluous legal rhetoric of law, which, in our age of disillusionment, can stain clinical progress. But we must remember this is nothing new. Physicians have always had to transcend their society’s constraints. It is not different from transcending our base instincts.

“Man is born free, but all around him is chains”, French philosopher Rousseau wrote when discussing the nature of man. Similarly, the physician is constantly fighting between strong and weak tendencies. These internal conflicts manifest in our clinical decisions: the decision to default to the most obvious clinical course of action or the decision to pursue one additional step towards certainty; and overcoming legal liability in favor of clinical principles that favors patient outcomes.

As the physician, so the profession: Medicine has always been beholden to the society in which it lives. In ancient Greece, medicine was bound to the triple relationship of science, gymnastics, and theology. Today, it is the tyranny of law manifesting through layers of byzantine administrative oversight.

The law’s grip over medicine is nothing new, though we like to think it is. It was anticipated a century ago. Indeed, such convoluted relationships have defined medicine throughout its history. More importantly, transcending these limitations has defined medical advancements.

None of which has come without first overcoming the societal struggle designed to keep medicine bound in place. Hippocrates faced competition from those who disagreed with his patient-centric approach to care. Osler faced competition from those who sought to look at medicine as only a science and abandon its art.

It is the mindset of those luminary physicians that defines the ideals of medicine today. But though their influence defines the practice of medicine today, their mindset is arguably more important, as it defines the ideals of medicine and should define our approach to law as physicians.

The best remedy against the encroachment of law is to embody the ideals of medicine. Ultimately, a physician’s behavior either succumbs to or transcends the adverse aspects of law. So, to beat the undue effects of law on medicine, put forth your best as a clinician.

It is that simple. It is that difficult.